The word 'game' immediately conjures ideas of play, entertainment, and light-hearted activities that seem off limits for learning about the Holocaust. However, games can be designed for learning and meaningful experiences and can contribute to thoughtful reflection on history and human behaviour. Part of the educational mission of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (hereafter, the Museum) is to challenge leaders and individuals worldwide to think about their role in society and to inspire critical thinking and self-reflection. There are many types of games (e.g., computer games, board games, puzzle games, role-playing games) and each offers valuable insights for imagining how one might design a game that helps to teach about the Holocaust without simulating or recreating the history in ways that lead players to draw oversimplified and inaccurate conclusions, but rather prompts players to ask questions that encourage critical thinking and lead to more nuanced understandings of history. The premise that a game about the Holocaust is off limits was worth exploring. Can games help achieve the Museum’s mission? In 2017, the Museum’s Future Projects team, which is tasked with exploring new technologies, approached games with an open mind and the question: What could we learn?

The Future Projects team is a small, internal team that prioritises experimentation over implementation, and builds prototypes to learn and ask questions. If the right conditions are present, including invested stakeholders and alignment with relevant Museum initiatives, a prototype may advance to full production. Most projects, though, are tested at a small, informal scale with staff, visitors, and other institutional audiences as circumstances allow.

The Future Projects team imagined that a thoughtful, engaging game about the Holocaust could be a powerful tool to reach audiences in a new way. We didn’t think that games as a category should be forbidden for teaching about the Holocaust. But as with any resource, the design of a game about the Holocaust requires a careful and deliberate approach. There are many elements of games that lend them to offering unique experiences for players to engage with Holocaust history and memory. Some of them are similar to visiting a museum, watching a film, experiencing a virtual environment, or visiting a website. Initially, playability can seem inappropriate, but it can also be understood as interactivity with systems – a way of understanding a world that would not be comprehensible by merely reading about or watching a representation unfold linearly. Believing that games offer a dimension and depth of interactivity for learning beyond that of traditional resources like books, films, and lectures, the Future Projects team created and facilitated several prototypes of games to better understand their limits and educational value. The team built on work in which Museum educators experimented with game-like elements in educational resources.

When we talk about games, we are including physical board games and digital games, as well as activities with game-like elements that create a sense of progression, participation, and achievement. We wanted to explore how games can address educational goals by encouraging engagement, immersion and a sense of 'flow'; offering positive reinforcement for learning and task completion; encouraging constructivist learning, critical thinking and problem solving; promoting collaboration and communication; and providing a shared experience and shared learning.

Approach

Part of our framework for understanding games comes from experiments with gamification in educational activities, as well as working with two game designers (Colleen Macklin and John Sharp) and their graduate students. As Macklin and Sharp describe in their book Games, Design and Play, 'Games are systems that dynamically generate play'. The experience of the game and the meaning of that play are determined by the player. Games create experiences that can elicit many different kinds of thoughts and feelings. As the Future Projects team embarked on an exploration of games, we started with the emotion and experience we wanted the players to have. What were the parameters we could set in place (the rules, if you will) that, as Macklin and Sharp say, would determine the substance and quality of the play experience?

The question of whether a thoughtful computer game about the Holocaust can reach a mainstream audience is beyond the scope of this paper. Here we will describe some of our efforts to date of ways we have considered the opportunities and challenges that games present when exploring their potential for Holocaust education and memorialisation. We will describe what we learned from our prototypes and explorations. Some were not strictly games but embody the ethos of a game experience or environment. We consider the affordances of games as a means to engage with Holocaust history. What can games do that books, films, and museum exhibitions cannot? What is inherent in playability? What do we want the player to experience (for example: storytelling, knowledge acquisition, skill building, or reflection)?

In addition to the challenges of Holocaust game design, new explorations must grapple with the ever-present management of institutional risk. The Museum is an authoritative source on the Holocaust and takes public trust very seriously, especially as a federal institution and the national repository for Holocaust collections and memory. While games have gained increasing acceptance as a medium, our institution has limited experience testing public-facing game-related projects, which could be interpreted in ways we may not intend by the visitors, donors, and staff essential to the success of our mission.

The Future Projects team approaches its work through the lens of learning and trying to understand the affordances, limitations, and opportunities of any given medium or technology. In addition to designing an appropriate experience, ensuring the rigour and accuracy of the history – and the quality of the experience – are important values that inform our designs. As Samuel Totten explains in Teaching and Studying the Holocaust (2001):

“The complexity and emotionally charged nature of this history dictates that not just any instructional strategy, learning activity, or resource will do. Each must be of the highest quality, thought-provoking, and not be comprised of those that, even advertently, minimise, romanticise, or simplify the history.”

Educational Activities

It is with this context in mind that we approached designing a game about the Holocaust. Prior to the establishment of the Future Projects team, the Museum conducted a few experimental educational activities in the digital space that informed how we approach games. We will describe two of those projects here – Children of the Lodz Ghetto: A Memorial Research Project and Witnessing History: Kristallnacht, the 1938 Pogroms.

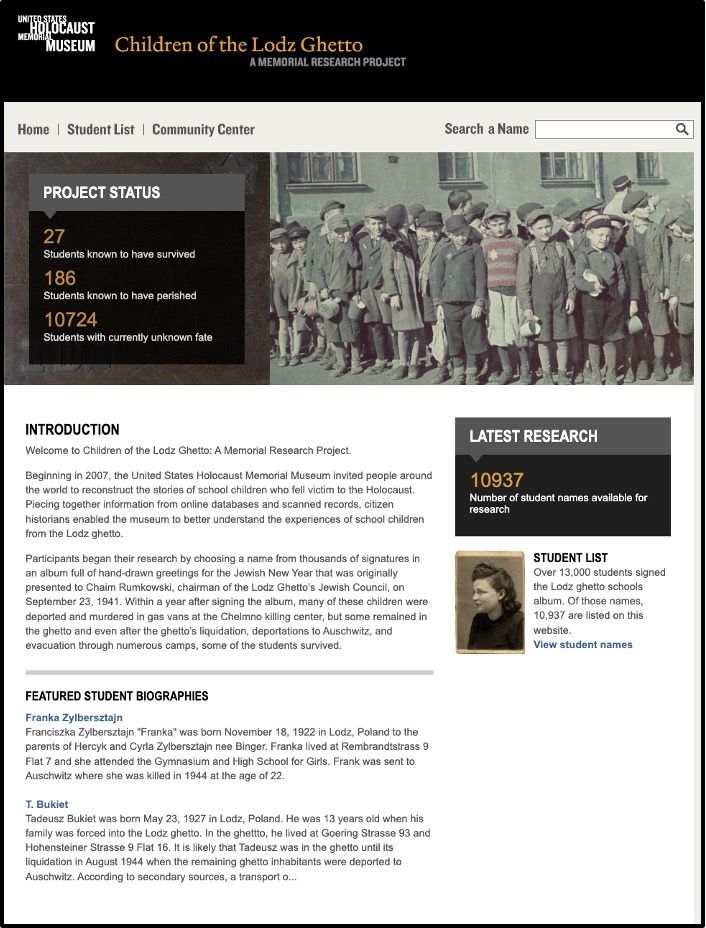

Children of the Lodz Ghetto

In 2007, the Museum launched a research project, called Children of the Lodz Ghetto: A Memorial Research Project, based on the idea of citizen science; we called it 'citizen history’. As described in an internal report, 'citizen' or 'participatory' history projects

“have the potential to engage non-experts in meaningful research by structuring their interaction with real data or source materials according to the needs of a larger research enterprise. 'Citizen history' falls into a group of projects known as digital learning, which are sometimes described as 'crowd sourcing’, 'tagging’, 'digital humanities’, 'crowd coordinating’, 'virtual curating’, 'humanitarian computing’, 'participatory exhibitions’, 'learning communities’, and 'collaborative pedagogy’. Learning takes place in the context of contributing to a larger goal. Participants tend to find satisfaction in contributing to a larger good, knowing that their work is meaningful and valued, and they often find status in their association with an 'important' project.”

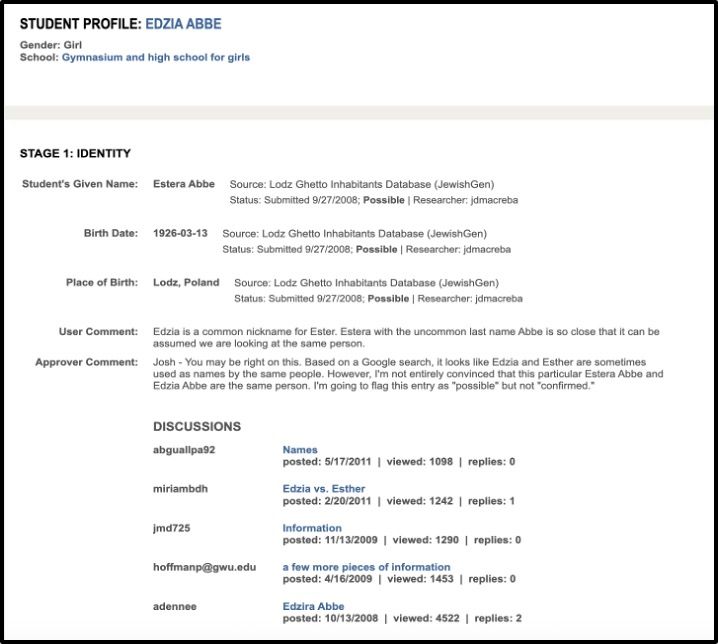

At its core, the Children of the Lodz Ghetto citizen history project was a digital environment that brought together a group of people to collaborate on a problem. Structured to promote scaffolded inquiry, Children of the Lodz Ghetto invited people to reconstruct the stories of school children who fell victim to the Holocaust by piecing together information from online databases and scanned records. Participants began their research by choosing a child’s name from thousands of signatures in an album from 1941. Within a year after signing the album, many of these children were deported and murdered; some of the students survived. The Museum was asking non-professionals to do history work and to find the story behind a name.

In a few important ways, Children of the Lodz Ghetto was structured like a game. The project was intentionally designed to engage participants to learn research skills. The activity and interactivity were set up within a structured environment where users proceeded through specific steps to attain mastery, as one might in a game. The goals were for participants to learn new skills, contribute to knowledge, and understand the abstract concept of six million victims as individual people. Participants were aware that their success helped to memorialise the individuals and reconnect their memories to the present, which functioned as a motivation for participants. Because their individual success was tied to the success of the communal effort, citizen historians' feedback to each other and to the Museum led the project to evolve over time and enhance the user experience.

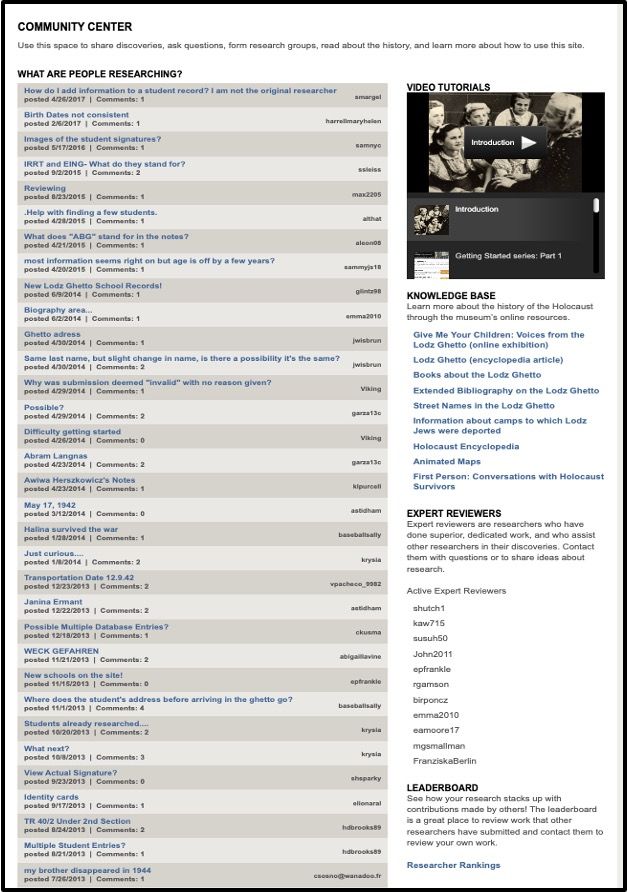

Some game-like elements in the project included: reward-based mechanics, such as a leaderboard, badges, and levelling up; a community forum and collaboration among participants and moderators; and establishing a clear goal and purpose for 'player' activity. As is critical in any successful game, the project included enough support and scaffolding by the Museum for participants to feel challenged but also for them to succeed (or 'win') at the task.

The 'task' itself provided a strong intrinsic motivation or value proposition for participants. The national authority on the Holocaust in the United States was asking for their help. The Museum didn't already know what had happened to these children. This was real research, and thus, every discovery that a 'player' made would effectively be understood by all 'players' and the Museum as a 'win’. This, combined with the memorial aspect of the project – reclaiming the histories of these children – provided extraordinary motivation for many participants.

The activity also allowed participants the time to be immersed in the experience. The activity gave them the opportunity to think about the history without having to recreate the history. Users learned about the history on their own in order to complete the research task – it was purposeful and meaningful. The project leaders thought about how to set up the context and tasks so participants could achieve at least some success.

One of the project’s successes was the creation of a research community. In addition to following their own individual journey acquiring new skills and knowledge, participants were part of a larger narrative in which they worked collaboratively to build a new body of research. Between 2008-2012, Professor Cayo Gamber integrated the Children of the Lodz Ghetto project into her undergraduate writing class at George Washington University. Students wrote about their experiences and the individuals whom they researched. Each year, Professor Gamber provided feedback to the Museum about her students’ experience with the project. Anecdotal evidence suggests that knowledge of history and research skills were more likely to be retained when acquired through an engaging, active and authentic process rather than a passive one. One of her students said, “we realised that even if we came to a dead end, that our research was meaningful in that it could get another researcher one step closer to finding more information about a certain individual”. Another shared, “selfishness flies out the window with this collaborative effort as individuals care not for personal recognition, but for the completion of this historical record, and ultimately for the increase of knowledge for the rest of humanity”.

In addition, secondary level teachers used the project in their classes and commented repeatedly on how powerful it was for their students to memorialise young people their own age by reconstructing their stories from available evidence and sources.

We applied what we learned in this experimental citizen history project to how we might design a game. We learned we could build a community within a digital environment that was centred around specific and personal research tasks. We learned that participants can learn about the Holocaust informally and in a self-directed way. And we learned they were motivated to add needed historical context to complete their specific research task.

Notably, game mechanics intended to provide extrinsic rewards – leaderboard, badges, levelling up – were of somewhat limited value. Rather, the addition of a community board for sharing information may have been the most valuable element. Intrinsic rewards, such as the knowledge that their actions were meaningful and that they were part of a shared community, were significant factors in 'player' engagement and motivation to continue. Equally important was the need for immediate feedback and evidence of their success ('wins'). Such feedback, whether from Museum staff or other researchers, reinforced that one’s contributions were valued. As a high school teacher in North Carolina told the Museum:

“This afternoon… my really low academic class was on the site, and they got so excited when your comments to them started showing up. This class has all kinds of issues and many of them do not do well in school and are never excited about anything we do in class. It was so wonderful to see them excited about learning. The instant gratification of hearing from you directly shortly after they posted information really engaged them in the site.”

Witnessing History in Second Life

In 2007, the Museum partnered with the youth civic leadership nonprofit Global Kids, and, together with high school interns at the Museum, developed an exhibition about Kristallnacht on the teen grid of the 3D virtual world of Second Life. Museum staff were sufficiently impressed by the potential of virtual worlds to engage visitors in a rich and interactive learning environment that the following year they worked with the firm Involve, Inc. to adapt the student interns’ design document to realise their vision on the main grid of Second Life.

In the resulting exhibition, Witnessing History: Kristallnacht –The November 1938 Pogroms, visitors took on the role of a journalist exploring a German street scene in the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht. The assigned task was to gather information, ostensibly to file a report afterwards. In the exhibition, visitors could visit a variety of spaces, including a store front, police station, school house, private home, hiding place, and synagogue. In each location, they learned about the Holocaust from documents, artefacts, historical photographs, and personal testimonies, as well as note cards that they could collect. In many cases, the visitors’ actions triggered animations or audio tracks through their movement or by clicking on items. At the end of the experience, visitors had the option to leave reflections for Museum staff and other visitors to read. The experience concluded in a video gallery of Holocaust survivors sharing the stories of their experiences during Kristallnacht.

There were a few key takeaways from the experiment with Second Life. Digital virtual spaces felt 'real' for participants. Their experience of being 'in world' and entering a distinct environment was tangible. When visitors made choices about how they moved through the environment, that engagement enhanced and informed the learning experience. The sense of immersion and presence – the feeling of being there and interacting with others as one might in a physical space – had a tangible effect on 'players’. Some of the features of Second Life that enhanced the 'player’s' sense of 'being there' also presented challenges to historical authenticity and a respectful memorial environment. For example, visitors to the sim would show up as their in-world personas. These were often cartoonish representations of self; sometimes human, sometimes animal, sometimes profane, but always invested by the 'player' with a sense of 'identity'.

In addition, the matter of 'player' role was an important one, offering agency and purpose without putting the participant in the role of a victim or perpetrator but rather in the role of witness. However, the role of 'witness' is an almost inherently limiting one. 'Player' agency was limited to choosing one’s own path through the sim, interacting with other 'players’, collecting data, and posting personal reflections at the end of the experience. As Julia Zungri states in her 2017 critique of Witnessing History, 'although Second Life is interactive in the sense that the user controls the avatar, interaction is ineffective if it lacks meaning. The user can click certain objects or scenes, such as graffiti on a wall to receive information, but, in this space, looking becomes more dominant than meaning-making’. In this respect, Witnessing History was more like a traditional exhibition than a 'game'. Nonetheless, these experiments (and the feedback they received) served as inspiration for future experimentation with games and game-like environments. The meaning-making was not necessarily inherent in the action.

Exploring Games

In 2016, the Future Projects team built on these insights of game design and educational activities and explored games more formally. Our goals were to improve our understanding of what games could do and how we would apply them to our mission; increase staff knowledge of and appreciation for games; and create several prototypes and test them with the public. We were aware of the controversial nature of the undertaking and the potential for games and informal activities to be seen as trivialising the history and memory of the Holocaust. However, a carefully and thoughtfully designed game or interactive experience could offer the opportunity to understand the complexity of a situation, or to elaborate on history in a way that could not be understood just by reading or interpretation. A game could have the potential to change an individual’s behaviour by allowing the participant to see an issue or event through a new lens or framework, to understand a situation differently, and to ask more questions and seek more answers.

The game Papers, Please by Lucas Pope (2013) served as an inspiration for the Future Projects team to explore games that can convey a meaningful story or feeling without replicating factual events and figures. We don’t think that a game about the Holocaust has to depict or replicate the history to teach effectively about the Holocaust. As an educational institution, the Museum’s guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust apply to classroom work as well as the resources we produce, such as films and exhibitions. These pedagogical guidelines informed our approach to game design, especially around the use of simulations. As stated on the Museum website:

“In studying complex human behaviour, some teachers rely upon simulation exercises meant to help students 'experience' unfamiliar situations. Even when great care is taken to prepare a class for such an activity, simulating experiences from the Holocaust remains pedagogically unsound. The activity may engage students, but they often forget the purpose of the lesson and, even worse, they are left with the impression that they now know what it was like to suffer or even to participate during the Holocaust. It is best to draw upon a variety of primary sources, provide survivor testimony, and refrain from simulations or games that lead to a trivialisation of the subject matter.”

If a goal of playing games is to win – and to master the rules to win – what are the rules we want players to master when playing a Holocaust related game? This is a vexing question if the player is situated in a realistic representation of the history: learning about the Holocaust should not be about feeling that one has experienced what genocide was like, so that shouldn’t be a core element of the game. At the same time, this begs the question of what we want players to feel and what we want them to learn from a game about the Holocaust.

A strong rationale provides focus and promotes understanding of the Holocaust as a complex historical event. Additionally, a strong, well-thought-out rationale provides structure and context for decisions that will guide game design and mechanics. Examples of common rationales for learning about the Holocaust include: encouraging players to reflect on the roles and responsibilities of individuals, groups, and nations when confronting the abuse of power, civil and human rights violations, and genocidal acts; providing context for players to explore the fears, pressures, and motivations that influenced the decisions and behaviours of individuals during the Holocaust; and understanding that the Holocaust was not an accident in history nor inevitable, and it occurred because individuals, organisations, and governments made choices that not only legalised discrimination but also allowed prejudice, hatred, and ultimately mass murder to occur.

New School Design Intensive

In 2017, the Future Projects team partnered with graduate students from the Parsons School of Design at The New School (Parsons) in a design intensive with the purpose of exploring the use of structured play and interactivity as a tool for extending the Museum’s educational mission. Museum staff provided the background and design challenges and participated in the testing and exploration of the game prototypes. Professors Colleen Macklin and John Sharp, co-directors of Parson’s PETLab (Prototyping, Education and Technology Lab), guided the students through the iterative design process. Some of the prompting questions the Museum posed to the students at the start of the design process were:

- How can a game help make a stronger connection between the events of the Holocaust and today?

- How fragile are the institutions of democracy, free speech, and freedom of religion that are considered the core of democracies?

- How can you recognise propaganda or hate speech?

- How can a game add nuance and complexity to learning a history that has no easy answers?

Over the course of a week-long onsite visit, the students learned about the Museum, its mission, and how it tells the history of the Holocaust. They spoke with staff, visited the exhibitions, and, in collaboration with staff, developed design values for this game design intensive. The students worked in small teams and created six game prototypes. Here, we will describe two of the prototypes – Joind and Pressing Matters. Both games pick up on themes important to understanding the Holocaust but do not depict it directly. These two prototypes were tested with the Future Projects team and Museum staff, as well as with some constituent audiences, including students and teachers. Although we did not formally evaluate these prototypes, the informal feedback helped guide us as we continued to explore games.

Joind

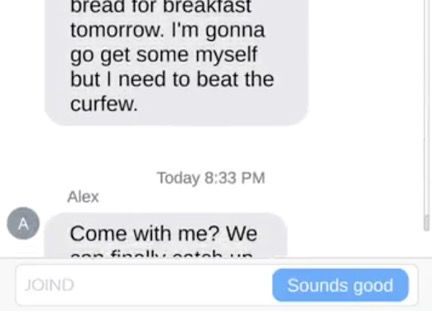

The prototype Joind is a mobile game that uses interactive storytelling to engage with the theme of being singled out and persecuted. The game design investigates the appropriateness of role-playing and was designed to convey the complexity of decision making and the impact of small actions. The player participates in a group text chat conversation that transposes a historical narrative into a modern context.

The player follows a few parallel text threads with messages that appear in rapid succession and must choose between selected prewritten responses to advance the story. The story, revealed through the text messages, involves a group of teen friends discussing an upcoming trip where something goes wrong and members of the group find themselves in danger. While the interactivity is limited, the game immerses the player in a visceral scenario. At the end of the game, the player watches a video clip from an interview with a Holocaust survivor, revealing the historical origin of the game’s events.

We tested Joind with young people as well as with teachers. For some testers, the game created a sense of connection and relevance, while others felt discomfort at the combination of modern fiction and historical fact, feeling it moved too fast and oversimplified the history. One of the students said, ‘everything that was displayed in the story made sense because during the real Holocaust things like this actually happened’. A teacher commented, “The use of survivor testimony at the end was laudable and it justified the narrative, but the comparison and bringing into the modern context was troubling”.

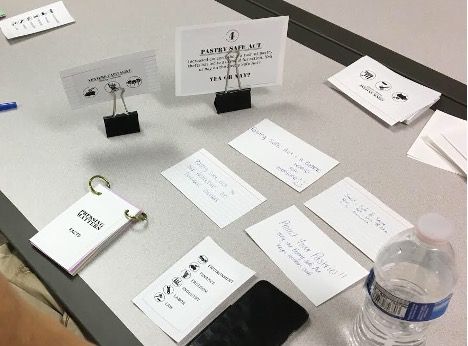

Pressing Matters

The prototype Pressing Matters is a tabletop social game that explores media literacy and propaganda. Players write headlines for publications with competing political goals in a fictional town. The game is played over a series of rounds, with one player in the role of a voter who scores the headlines, while the rest are writers for each publication. The writers randomly draw an issue card and write headlines based on that issue. Players score points by writing headlines that convince other players to vote the way they want them to on a particular issue. Each player takes turns being the voter.

We also tested Pressing Matters with young people and teachers. We found that the game’s initial complexity was a barrier to entry, and the creative demands of writing headlines appealed to some while frustrating others. Some felt the game did a good job of allowing players to interact with topics like propaganda and media literacy in a competitive format.

One student said, “I think the game is about learning how much influence words can have. Words can be deceiving. If the right person uses the right words, it would be easy to lie and manipulate others”. Another student said, “I liked that the game makes you think, but it's at the same time fun. I think it's a pretty creative way of teaching/making people reflect on real life issues”.

Some teachers were less sanguine. One said, “while it demonstrates and involves students in creation of propaganda, the relationship to the Holocaust and genocide is loose. It also poses the danger of simplifying an issue – posing societal issues (which are important) and not showing the danger of vitriolic rhetoric. That being said, in a civics class, this might be more accessible”. Another teacher commented, “Without a solid discussion or lesson that connects this to the rise of the Nazi party, it would be hard to connect. If that is included with this activity, it could teach a lot about the role of the media in the Holocaust and generating support”.

Internal Projects

We built on the learnings from our previous work and prototypes with Parsons to continue to investigate what a game experience could look like. We wanted to approach the medium of games from different angles to learn more about their potential. The following internally developed prototypes, Exodus and Inquest, are examples of this inquiry – one is a tense board game experience, and the other a more relaxed digital history puzzle.

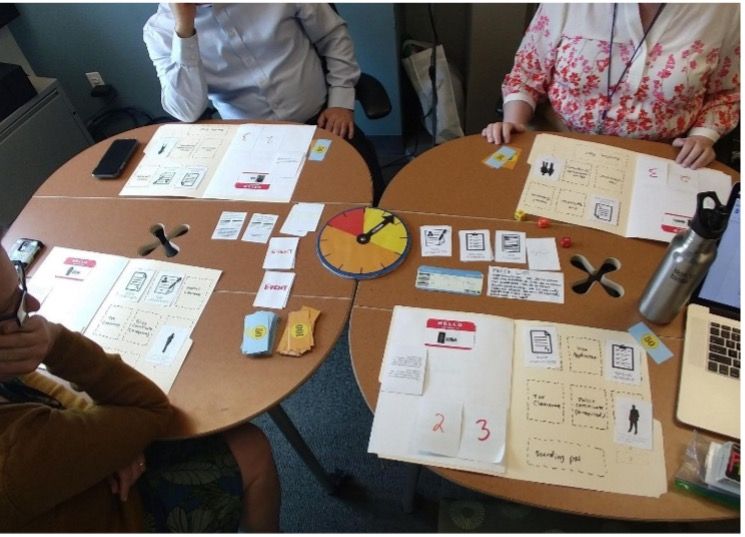

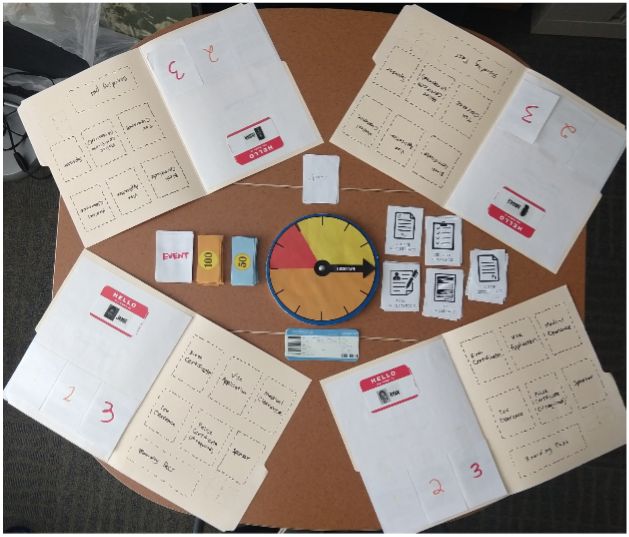

Exodus

In 2018, we created Exodus, a board game prototype that addressed one of the questions educators tell us is asked very often about Holocaust history: 'why didn’t the Jews just leave?' Exodus is designed to enable players to experience the tension and uncertainty of navigating an emigration bureaucracy like that of Nazi Germany. The game was inspired by the card game Fluxx and the content of our special exhibition, Americans and the Holocaust. Four players attempt to escape a fictional country in turmoil by assembling a complete portfolio of documents while coping with unpredictable events, limited resources, and a narrowing escape window. Successful escape is possible but very difficult and subject to the whims of chance events.

Early on, we decided to base the prototype in a fictional setting similar to the Holocaust instead of trying to create an accurate historical scenario. This sped up development and gave us the creative leeway needed to prioritise the quality of the game design. To ensure the game experience didn’t feel like an exercise in futility, we took care in adjusting the difficulty so that success felt possible but avoided an 'everyone wins' scenario that could send the wrong message about how decisions impacted the fate of victims. The random nature of the event cards kept uncertainty high without removing the player’s ability to impact the outcome.

After limited staff testing, a key takeaway of the Exodus gameplay was that the tension of the game elements, such as time limits and random events, were effective at engaging players, creating urgency, and offering an emotional bridge to the history. Another learning was that the rules and goals were almost too complex for some players, though this was mitigated by having someone well-versed in the rules running the game and clarifying how things worked.

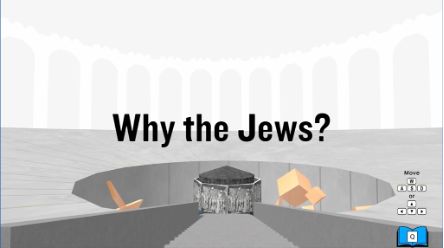

Inquest

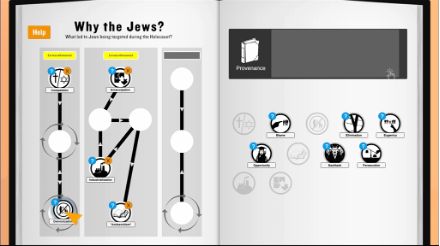

In addition to the question 'Why didn’t they just leave?', there are many others that are often asked. In 2023, we were inspired by Peter Hayes’ book Why? Explaining the Holocaust (2018) as a framework for exploring these questions in a game environment. Inquest is a digital game prototype designed to explore the potential of puzzle games as a curiosity building experience. It takes inspiration from puzzle games like The Case of the Golden Idol and Chants of Sennaar, giving players a space to explore and locate pieces of the puzzle (historical events, recurring phenomena, and other factors) using information they find to determine how the pieces fit together.

Players navigate a dream-like memory space, finding fragments of memory related to Holocaust history that they assemble in a flow diagram in their in-game notebook. Solving parts of the puzzle allows further progress and exploration. Early in the concept design, the idea of 'reverse engineering' the relationships of these historical factors was compelling but care was needed to ensure that the puzzle aspect didn’t feel like you were 'rebuilding' the Holocaust, resulting in a reduction of 'machine-like' qualities to the puzzle design.

The Inquest prototype is still in active development with limited staff testing, but takeaways so far include that puzzle design must be carefully calibrated to avoid extreme difficulty; that some players have trouble with 3D navigation; and that the exploration and puzzle elements need more integration to create a cohesive experience. The unique thematic lens of the prototype’s content on the history of antisemitism led to most testers learning new things, feeling the exploration and puzzle mechanics were a welcome interactive aspect to engage with the history. Testing a new iteration with members of our student program will take place later in the summer of 2025.

Conclusion

Games about the Holocaust can use a variety of strategies to engage players with the history – offering meaningful interactions, creating an immersive environment, and connecting past and present. In our experience, we have found more room for game design creativity and innovation by putting the player in post-Holocaust scenarios rather than placing them in historical roles. This eases many problems with making a functional, engaging game by not requiring every aspect be based on documented historical people, artefacts, or situations, and more easily permits integration of fictional elements that can be very useful to the game design process.

Throughout the projects presented in this paper, we have explored a variety of Holocaust history games and game-like experiences, demonstrating different ways a post-Holocaust setting can be used. In Children of the Lodz Ghetto, Witnessing History, and Inquest, players adopt the role of investigators, seeking to fill in blanks or synthesise information. In Pressing Matters and Exodus, players interact with systems in a fictional setting modelled on historical events to better understand their challenges and impact. In Joind, a modern fictional story links to real survivor testimony as a way to connect the experiences of young people today with those during the Holocaust. By focusing on post-Holocaust scenarios, we were able to create interesting experiments and could iterate quickly because the game did not rely on finding the 'right history' to justify the game concept. This approach also offered a wider window of appropriate success scenarios and helped us mitigate institutional risk. By learning through experimentation and testing, we can create innovative educational opportunities that take advantage of the playability and interactivity of games.

As one of the leading Holocaust institutions, the Museum takes its role very seriously in the design of educational resources. Designing games of the calibre expected requires support and expertise beyond what is available in-house. However, learning as much as we can about games, design, and engagement will equip staff to have stronger partnerships should the Museum decide to pursue the implementation of a game for public distribution.

We conclude with the following questions:

- How can we create games about Holocaust history, especially those involving choice and strategy, that reward and encourage players without sending the wrong message about 'winning'?

- Is completion a viable alternative to winning?

- Pedagogical questions: What are players doing and why? What do we want the outcomes to be?

- Is there a role for AI in games as a director/moderator to keep the players from moving in inappropriate directions?

Author Bio: Silvina Fernandez-Duque, David Klevan and Russ Sitka

Silvina Fernandez-Duque is Future Projects Manager at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. As part of an innovation lab team, she explores the potential of emerging technologies in museums, researching and prototyping new experiences for visitors and learners, with a particular focus on difficult history.

David Klevan is Education Outreach Specialist at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He leads outreach to U.S. state curriculum supervisors and administrators. His knowledge of experiential and constructivist learning informed a variety of digital learning environments, including History Unfolded, Children of the Lodz Ghetto, and Witnessing History: Kristallnacht in Second Life.

Russ Sitka is lead designer and developer of interactive experiments in Future Projects at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. His work incorporates multi-disciplinary creative and technology skills to prototype new experiences, research new techniques and technologies, and explore possibilities to enhance how history is felt, understood, and transmitted.