For some time, it felt like games may be the last taboo of Holocaust representation (Kansteiner 2017). As the number of television and cinematic depictions of the Holocaust grew, criticisms of these formats diminished. In debates about NBC’s Holocaust (1978), Schindler’s List (1993), and Holocaust comedy (see for example, Elie Wiesel 1978; Shandler 1999; Hansen 1996; Des Pres 1988), academics and commentators argued that popular media condense complex histories, present unrealistic depictions of victims, and do not respect the solemness of this past, its uniqueness, and unrepresentability. Nevertheless, as the twenty-first century progressed, academics began to acknowledge that each of these media forms has its own specificities and is always limited in terms of what it can depict (Baron 2005). Debate shifted from whether the Holocaust could and should be represented in popular media to the ethics of different approaches (Saxton 2008), and whether representation might be the most useful lens through which to study these approaches at all (Walden 2019). This latter challenge has become more poignant with digital media (Walden forthcoming).

Simultaneously, emerging practice in computer games was causing controversy. Whilst some representational issues continued to be articulated (e.g., the fear of glorifying the aesthetics of Nazism, see Freidrich 2020), the core concern was with the very premise of the medium: its playability. In the mainstream industry, ‘Nazis’ had long featured in war games and most famously the Wolfenstein series, yet until 2023 there existed no game on any of the major consoles which took a serious approach to depicting the Holocaust. The closest attempt was a brief segment of Call of Duty: World War II, but here player controls were disabled reducing them to a viewer (Marrison 2020). It was not the case anymore that the Holocaust was considered ‘unrepresentable’, but rather that it was regarded as ‘unplayable’.

In 2013, Indie gamemaker Luc Bernard tried to raise funds to make the fantasy game Imagination is the Only Escape via the crowdfunding platform indiegogo.com. The narrative would have followed a young boy’s attempt to find solace within his imagination during the horrors of the Holocaust (not dissimilar in premise from the Academy Award winning feature film Life is Beautiful [La vita è bella 1997]), yet the international press lambasted his idea to the point it was abandoned. Likewise, a young Israeli, who attempted to mod one of the Wolfenstein games to present a Sonderkommando Revolt – to depict strong Jewish characters rather than repeating the trope that all Jews were weak, passive victims – also faced such public backlash that he became a recluse (Another Planet 2017). Criticism of Holocaust computer games at this moment seemed legitimised by the use of game formats to create denialist content such as KZ Manager. Yet as historian and memory scholar Wulf Kansteiner (2017) notes, such dismissal of the medium as a serious space for Holocaust commemoration and education means ‘the field is left wide open to dubious right-wing concoctions’ like the example above. Simply put, by doing nothing in gaming spaces, Holocaust experts have become complicit in enabling denial and distortion to grow across gaming culture by offering no alternatives. Thus, examples like KZ Manager –never actually released as a full game – are not reasons to avoid the medium of games, but illustrative of what happens if it is ignored as a space where more productive engagements with this past can be explored.

Against this background, game spaces – particularly the open world-building platform Second Life were being used by at least one well-established Holocaust organisation. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum built the exhibition Witnessing History: Kristallnacht, the 1938 Pogroms here, part of a wider culture of museums, galleries and universities adopting the platform to create virtual exhibitions and classes. Yet, despite the careful and deliberate curation designed so as to prevent players feeling like they could travel back in time, change the course of history, or experience the pogroms for themselves, it was still received with some hesitancy, criticised for the potential to give users the experience of a prosthetic engagement with this past and thus a ‘spectacularization of trauma and memory’ (Trezise 2011). Although it is not clear how such criticism demarks such virtual museums in gaming spaces as distinct from similar physical exhibitions in museums, including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum itself, which can also present spaces which give a fragmentary impression of historical environments.

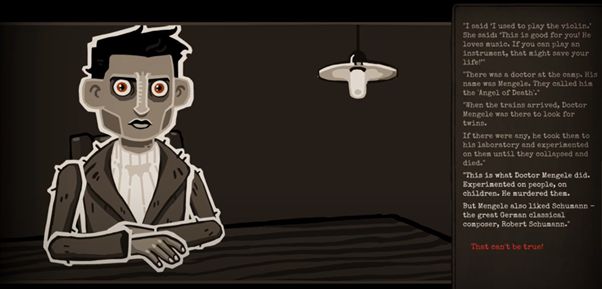

A smaller Holocaust memory charity based in Scotland, United Kingdom – Gathering the Voices has long been leading the way with experimental media practices. In 2013, just as Bernard’s game idea was appearing on indiegogo, Gathering the Voices partnered with students and survivors to lead a 48-hour game jam, designed to create interactive, playable stories that were ‘faithful to the source material’ of the charity’s testimony archive (Moffat and Shapiro 2015). Despite a series of challenges, especially in terms of technological obsolescence and funding, they have recently launched the award-winning Marion’s Journey, with subsequent projects Suzanne and Mercy Squad at different stages of development. The one released game - Marion’s Journey - provides an interactive narrative engagement with the testimony of survivor Marion Camrass. Gathering the Voices’ work, however, did not gain the international press attention which Bernard and the Sonderkommando Revolt mod attracted.

Now, it seems Holocaust computer games have become legitimised; they are no longer taboo in themselves. One notable recognition of this has been the change in promotional language used to describe the National Holocaust Centre’s (UK) Journey app, once called an ‘interactive story’ (Walden 2021), it is now confidently described as a ‘game’ on the Centre’s website. Alongside this, since 2012 the Stiftung Digitale Spielekultur (Foundation for Digital Games Culture) has been building bridges ‘between the world of games and political and social institutions in Germany’ (as per their mission statement). A significant part of this work was the ‘Remembering with Games’ project. This programme advocated for, educated about, developed recommendations on, and tracked how games can deal sensitively with the Nazi past as well as other poignant memory cultures.

Whilst not exclusively about Holocaust games, the Imperial War Museum’s War Games: Real Conflicts, Virtual Worlds, Extreme Entertainment (2022) was the first exhibition in the UK to explore the relationship between video games and conflict, and featured Through the Darkest of Times and Wolfenstein 3D, a talk by John Romero (one of the creators of Wolfenstein), and a game jam hosted in partnership with the Historical Games Network. In 2022, the Digital Holocaust Memory Project – the precursor to the Landecker Digital Memory Lab, here at the University of Sussex – ran a series of co-creation workshops which led to the development of recommendations related to digital interventions in Holocaust memory and education, one of which was dedicated to computer games and play. This workshop series hosted 26 participants, from across academia, the Holocaust heritage sector, and the games industry including representatives from the Historical Games Network; Stiftung Digitale Spielekultur; the German civil service; and Luc Bernard, as well as Angela Shapiro from Gathering the Voices.

Whilst computer games are clearly no longer taboo, in principle, there is nevertheless, still only one game dedicated to the experiences of Holocaust victims available on mainstream consoles – Luc Bernard’s Light in the Darkness (a more historically-grounded game than his original 2014 proposal). He has also created a Holocaust museum in Fortnite called Voices of the Forgotten with the support of Epic Games. Most Holocaust-related games are otherwise created through two indie companies, the first a spinout of Charles University, Prague Charles Games and the second based in Germany, Paintbucket Games. The former developed their first related game Attentat 1942 with embedded pedagogical aims and carried out substantial impact analysis in classroom studies. Whilst the latter has recently worked directly with Holocaust organisations, for example on Remember. The Children of Bullenhuser Damm in partnership with the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres Commemoration the Victims of Nazi Crimes, promoted as a ‘digital remembrance game’.

This concept of a ‘digital remembrance game’ speaks to the emergence of what I define as a typology of Nazi-era computer games:

- Remembrance Games – position players in a post-Holocaust period, requiring them to investigate the past. (Attentat 1942, Remember. The Children of Bullenhuser Damm, The Darkest Files, #LastSeen and Nowolipie 29D).

- Museum Simulations – create ‘virtual’ museum experiences in gaming spaces (Witnessing History: Kristallnacht, the 1938 Pogroms, Voices of the Forgotten – the Holocaust museum in Fortnite).

- Historical Games about the Nazi Past – this type includes different sub-categories. For example, combat games – whether fantastical or more historically-grounded, which are focused on combat and strategy, tending to be First-Person Shooters (FPS) (Call of Duty: World War II and Wolfstein series) or strategy games (Hearts of Iron). Then, those that are about the Nazi-era more broadly, sidelining or abstracting the Holocaust and/or Jewish characters (The Darkest of Times, Forced Abroad, Svoboda 1945: Liberation, Train to Sachsenhausen: Student Protests of 1939, and My Memory of Us). There are also those games that explicitly allow the player to take on the role of or at least follow the experience of a Jewish protagonist (Marion’s Journey, Light in the Darkness, Journey App). This latter sub-category remains the least represented.

Earlier criticism suggested that major games have only ‘teetered on representation of [the Holocaust], often taking liberty with Nazi themes while placing the Holocaust within the margins or completely eliding the persecution of European Jewry altogether’ (Walden, Marrison et al. 2023, referring to Hayton 2015; Chapman and Linderoth 2015; Marrison 2020; van dan heede 2023).There is evidently still hesitancy about making the Holocaust actually playable. As illustrated above, many existing games – especially those which allow players to roam through a game world, and make choices – either push Jewish individuals, experiences and narratives to the sidelines or are set in post-Holocaust contexts. There is also a tendency to limit interactivity and the ability for players to make choices or roam through simulations of historical spaces. For example, Train to Sachsenhausen uses the mechanism of the dating app Tinder, offering players a ‘swipe left’ or ‘swipe right’ option for each moment in the narrative, but the historical scenario is presented simply as a set of swipeable cards, not an explorative game world. Furthermore, games that do allow players to follow a Jewish protagonist, stop short of making spaces of confinement and mass murder playable. Thus, they only really present the pre-Holocaust narrative, not the spaces that define this past as genocide.

One potential rationale expressed for such hesitancy is that games are designed for younger people. However, this is a misunderstanding of the gaming sector, with a large proportion of today’s players being those who grew up with the earliest domestic consoles. Similar assumptions were made about comic books and graphics novels, and now we see an increasing number of Holocaust-related narratives explored through these media.

Furthermore, ‘interactive’ experiences are assumed to offer players the potential for free reign in game worlds which ignites fear about players having the potential to re-write history. However, all game experiences are heavily curated by the developers and designers, even sandbox worlds for which the creative team have made conscious decisions about making these open worlds, yet there are boundaries to the playable spaces and limits to the types of actions players can do in them (even if they seem limitless). What distinguishes games and broader ‘playable media’ from broadcast media is the fact that they combine both narratological and ludological logics. Completely ignoring the ludic possibilities of games for the sake of a clickable, linear story or providing very limited choices through a simple decision-tree formation, as many Holocaust-related games currently do, resists the very ontology of ‘game’ and raises questions about whether game aesthetics and platforms need to be used for the desired outcome. Currently, it still seems the more games engage with victim experiences of the Holocaust, the less interactive opportunities they offer players.

In transitioning from the fantastical Imagination is the Only Escape to Light in the Darkness, Bernard felt he had to make compromises – that a mainstream computer game about the Holocaust would only be taken seriously if it acknowledged the hesitations of those in the Holocaust memory and education sector. Yet, this game still pushes boundaries – offering not only the first Holocaust computer game on a console (PS5), but the first to follow a Jewish victim in Vichy France through the historical actions of the 1940s. Nevertheless, one of the compromises Bernard made was in terms of interactivity, so like many of the existent Holocaust computer games, Light in the Darkness is styled as a point and click story where players are offered the choice of a series of phrases to move on dialogue, similar to the National Holocaust Centre’s Journey app (which as we have seen was once described on their website as an ‘interactive story’).

What is at risk if practice continues in the current direction is that so-called ‘serious games’ about the Nazi-era grow in number, but the Holocaust and the experiences of Jewish, as well as Roma and Sinti, victims of genocide are erased. With this, stereotypes of the ‘passive’ victim continue to perpetuate, and the dominant message computer games will present is that only those who engaged in acts of resistance or perpetrators had agency. This perspective goes against the grain of developments in Holocaust education and memory, which have sought to present the complex range of diverse experiences and to centralise victim’s narratives. Whilst victims may not have had control over their fate, they were - as all actors during this historical period were - complex human individuals, who made choices based on how they perceived their current situation. Some took risks which saved them or endangered their lives further, others survived due to sheer luck in the timing at which they decided to flee or in which their immigration papers were processed.

The question remains, would the majority of Holocaust-related ‘games’ currently available be better described as interactive literature? Have we actually created any computer games about the Holocaust yet? Games are cultural systems, both each game in themselves and as part of a wider gaming culture. They rely on ‘contact by interaction’ (Mäyrä 2008), but importantly this interactivity is not only with other people but with computer systems (Huhtamo 2000; Calleja 2011) and a virtual game world through the avatars we take on in embodied, performative ways. For Huhtamo, human input should be rapid and not overthought, so that the human and computer contributions to the interaction are equal and symbiotic. ‘Gameplay embodies the rules of the game’ (Mäyrä 2008), thus games are ‘procedural’ – the computer systems behind games run processes and execute rule-based symbolic manipulation, and enable us to explore simulative environments which invite us to interact with these systems and make judgements about them, the worlds they represent, and the affect, messages and values they may evoke (Bogost 2007). Part of the player’s mission is figuring out how to game the game, e.g., how to master its rules to win. What differentiates games from other forms of storytelling is their ludic nature. Their meaning-making comes ‘through playful action’ not simply representation (Mäyrä 2008). Furthermore, the ludic nature of games constantly shifts players’ attention between the diegetic game world and the extra-diegetic interface and computational control unit with which they must engage to play the game. Interactive literature on the other hand - just as with their novel-based counterparts - attempts to immerse the user/reader into the story world (the diegesis). Interactive literature gives players the sense of choice over how the story unravels within a limited framework – there is no game to game, no rules to master. In contrast, computer games make players explicitly aware that they are engaging with computational processes, rule-based environments, and systems beyond the game world as much as they shape it.

A computer game then could simply be defined as an interactive encounter between player, represented game world, and computer system (or systems) in which meaning is made through playful actions situated within a particular rule system, which the player must master to win the game. In the recommendation workshop held as part of the Digital Holocaust Memory Project (introduced earlier in this provocation), participants agreed that the following are affordances of games:

- ‘Unique mode of storytelling. With the capacity to contain multiplicities, offer multi-vocal perspectives and to zoom in on individual and untold stories.

- Encourage active and investigative learning. Framing the player as an active agent who can make decisions and take responsibility for their own experience and memory practices.

- Experimental, imaginative and experimental encounters. Allows for new pedagogies to be developed within the Holocaust memory and education sector, that are centred on actively doing something, participatory as eye-witness testimony begins to fade and we prepare to transit into a post-survivor age.

- Processes, people, projects. Game design processes themselves create new ways of doing things with, funding, and curating Holocaust resources, materials and narratives. They offer the opportunity to bring together a wide range of professionals and publics, and merge the research and tech sectors in ways that will be integral to the future of digital Holocaust memory work.’

The very ‘interactivity’ which is crucial to defining a game as a game then lingers as a concern, particularly in relation to the potential for players to change the course of history, or to be able to make choices in simulations of historical spaces related to mass murder and the dehumanising practices of death camps, concentration camps, ghettos and beyond. Thus, as I have argued elsewhere, we are seeing a shift from debates about the ‘limits of representation’ to the ‘limits of interactivity’ (Walden, forthcoming). Although, as I also suggest in the same piece, we should reframe this as the ‘possibilities of interactivity’.

Whilst Holocaust memory and education organisations now seem comfortable with the semantic descriptor ‘game’, taboos concerning playability and interactivity still seem to remain.

In this, our first Dialogue, I pose the following questions to the respondents and ask that they provide rigorous but reflective responses, considering lessons learnt from their own work, as well as reflections on wider game practice and research in our field.

- How much have we really moved on from those earlier days when Holocaust computer games were forbidden?

- What is at risk if we engage more with the specificities of computer games as interactive, playable media?

- How can we understand the possibilities of interactivity in game contexts?

- What is at stake if we do not take the specific affordances of computer games seriously?

- What have we learnt through the brief history of Holocaust computer games to-date?

- Why make computer games about the Holocaust? (What impact analysis shows that this medium works with any particular target group?)

- To what extent do existing Holocaust games make this past ‘playable’, ‘modular’ and ‘variable’, or do these possibilities remain taboo? Are there any red lines that are impossible to cross in designing computer games about this past?

- From your own practice, are Holocaust computer games suitable for placing visitors into simulations of historical scenarios or better for positioning them in post-Holocaust situations, where their role is to be memory or history investigators?

- Currently, the majority of Holocaust computer games decentralise Jewish characters, e.g, they are often not the protagonist or made playable for the user. Are we at risk of minimising the ‘voices of the drowned’ in the current approach to Holocaust computer games?

- What would be a productive future for the development of ‘the Holocaust’ as a subject matter for mainstream gaming, and what would be needed to get there?

Credit for opening banner image: 1 screenshot from Witnessing History: Kristallnacht in Second Life. ©️ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Screenshot provided by David Klevan. 1 screenshot from #LastSeen, an example of a remembrance game. ©️ andwhy. Image provided by Alina Bothe. 1 screenshot for The Darkest of Times. ©️ Paintbucket Games. Image provided by Jörg Friedrich.

Author Bio: Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden is Professor of Digital Memory, Heritage and Culture, Director of the Landecker Digital Memory Lab and Deputy Director of the Weidenfeld Institute for Jewish Studies at the University of Sussex, UK. She is Editor-in-Chief of Digital Memory Dialogues.