With this response, I wish to place two concepts at the centre of discussion, and highlight their unique significance for memory discourses: interactivity and agency.

We are always in a position of ‘post’ when approaching Holocaust memory: on the one hand, our access is mediated, post-framing the past. On the other hand, our experiences are shaped by living in a time ‘after’. Thusly, we are always depending on systems beyond our individual engagement to gain access to cultural memories. However, we are also never purely passive in these processes. Rather, we are involved – cognitively, emotionally – and hold agency.

I argue that our engagement with the Holocaust in memory cultures is driven and shaped by what I perceive as ‘post-agency’. I understand post-agency as our potential to participate in processes of cultural remembrance, to be actively involved in them. Post-agency manifests at the intersection of our individual identities, our bodies, discourses of memory culture, and media technologies.

Our agency as ‘post’-actors of remembrance enfolds on multiple levels. It is a distanced agency, enraptured and slippery. Drawing on Marianne Hirsch’s notion of postmemory, such agency can, in my point of view, be grasped as a delayed, distanced and mediated agency which is nonetheless there, attached to our bodies and perceived identities. As Hirsch argues in her monograph The Generation of Postmemory, postmemory becomes, through bodily symptoms, a process ‘[…] of repetition and reenactment, and, on the other hand, one that works through indirection and multiple mediation.’

Repetition, reenactment and mediation – these are the factors shaping my understanding of such a post-agency that can be traced in the ways we actually interact with memory discourses, how we participate in them. Of course, in digital memory cultures, such agency is strongly influenced by the ambiguous structures of digital media, shaped both by individual decisions and technical forces. I will go into this aspect in more detail later. For now, the ‘post’ aspect of digital media’s influence on the user’s possibility to enact their agency lies in the systematic structures that underlie all digital interactivity: while users have the ability to make choices and act, their actions are often influenced by the invisible algorithms and attention economies that govern digital platforms. Thus, agency in the digital space becomes a complex interplay of autonomy and technological influence, where the boundaries between free will and algorithmic control are blurred.

Interactive settings in games can serve as powerful, creative, and experiential spaces through which we become particularly aware of our post-agency. Moreover, interactive game settings enable us to trace this post-agency’s various dimensions, offering a more concrete understanding of different modes of engagement with the past.

Thus, with this response, I aim to further explore the specific relationship between interactive moments in digital gameplay and our memory-cultural agency as members of a ‘post’-collective. By introducing the concept of post-agency, I seek to offer a term that may meaningfully connect the ambivalences between body and media technology, distance and proximity, as well as the virtual and the analogue. This may contribute to a deeper understanding of our own involvement with the past through digital media.

In my argument, I draw on findings from my own research on games as media of remembrance, as well as on my professional experiences with the project ‘Let’s Remember!’ of the Foundation for Digital Games Culture and, additionally, the exhibition Choose your Player at the Zeppelin Museum on Lake Constance.

Post-agency and the Concern for the ‘ing’ in ‘Doing Memory’

Interactivity can serve as a vital key element in activating digital users as agents of cultures of remembrance. This conviction is based on the idea of cultures of remembrance as a transgenerational community, connected through shared practices: passing on, taking care, preserving – these are all calls to action. Or, following the logic of post-agency, they represent moments in which involvement is realised through engagement, and our potential as post-actors of remembrance is actualised.

I understand ‘never again!’ as a repeated call for responsibility that must be renewed and redefined over time, in an ongoing process. Thus, as I have argued previously, I strongly advocate for a shift towards the ‘ing’ in memory cultures. The present participle in English achieves something linguistically that is difficult to express in German; namely, placing emphasis on the temporal span and processual nature of an action, which is tied to repetition and continuity. It might be even more accurate to speak of cultures of remembering or even of culturising memories, rather than memory cultures or cultures of remembrance: they represent the results of actions and contributions that have actually been made. Consequently, I perceive the ‘ing’ as the driving force of memory cultural processes. It can be framed as the ongoing actualisation of actors’ post-agencies.

Accordingly, we urgently ask ourselves where these agencies are leading us. What outlets and spaces for shaping cultures of remembrance are available to us? And conversely, what values, beliefs, and agencies become visible through our practices?

That these questions lie at the heart of contemporary memory cultural work has been particularly evident in my involvement with the ‘Let's Remember!’ project. As part of the initiative, we conducted on-site training sessions on the use of digital games, which repeatedly brought us into contact and dialogue with staff from various memorial sites across Germany.

One of the main concerns expressed by those deeply involved in Holocaust remembrance and its mediation is how future generations can be actively engaged in cultures of remembrance and how digital media might shape their attitudes towards memorial sites or educational contexts. Does a game experience genuinely influence a player’s attitude towards places of remembrance? And if so, how? What kinds of actions can foster proximity, connection, and a sense of meaning within memory-cultural processes?

At the same time, another recurring question in these discussions is how to highlight the fact that even every day, seemingly banal actions contribute to cultures of remembrance. What commemorative stance do I take when I ‘like’ a video dealing with Holocaust remembrance? What position does the video itself adopt? And what position do I, in turn, express through my interaction with it?

Put differently, these questions all revolve around how to activate awareness of one's individual post-agency, seeking channels and forms of expression that can reactivate and renew remembrance: What forms of expression do contemporary generations have for their memory cultural post-agency? An agency that is undeniably ascribed to them, as the relevance of the past is regularly presented to them, and their own relationship to it is acknowledged? And how, simultaneously, can we encourage reflection on post-agency that is already being enacted, consciously or unconsciously, through digital media consumption?

Gamed Interactivity: The New Dimension in Holocaust Memory

With the rise of digital games, a new medium of memory has entered public discourse –one that sets itself apart from traditional forms such as photography, literature, film, and television series. What distinguishes games most profoundly from these established memory media is their promise of interaction with the historical setting they create. Unlike linear memory media, which present a structured narrative shaped by their respective formats, video games open up the space for ambiguity and relationality through interactivity. Especially avatars, as Rune Klevjer has argued in his groundbreaking research, which are primarily ‘mediator[s] of agency and control’. Therefore, players’ involvement forms an essential aspect to the medium ‘videogame’.

For experiencing a historical or memory cultural setting in games, this means rather than offering a singular interpretation of historical memories which every player will receive equally, they create spaces of engagement where meaning is fluid and shaped through the game play.

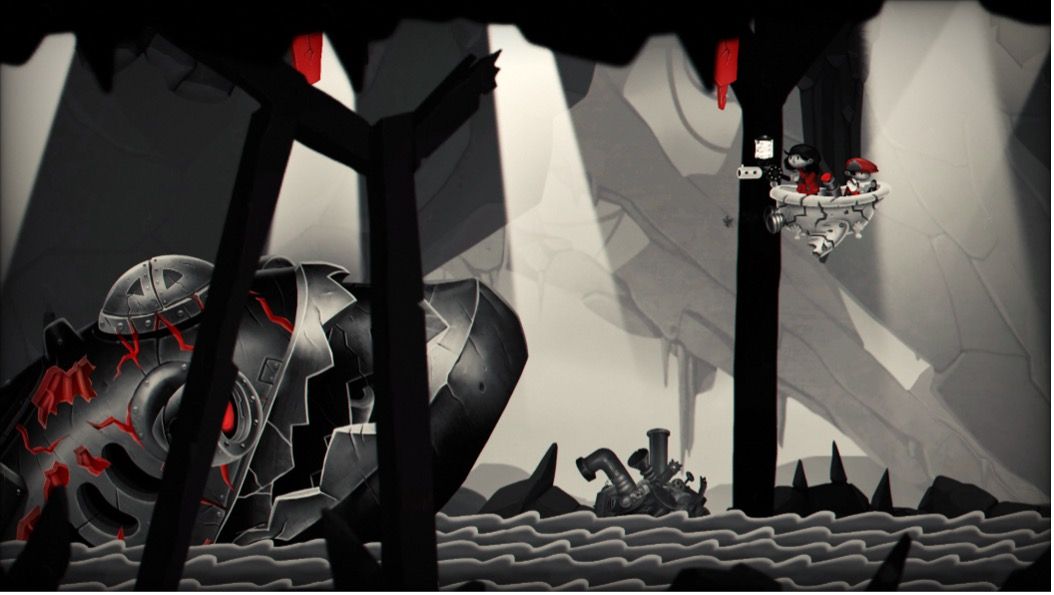

For example, the videogame My Memory of Us introduces us to two children, a girl and a boy. The players are tasked with saving them from a robot army that invades their hometown. For those with sufficient historical knowledge, the game’s storyline is transparent as a metaphor for the invasion of Warsaw by Nazi Germany and the ghettoisation of the Jewish population living there. Simultaneously, some players might identify the character of the young girl in the red coat – in this screenshot (Figure 2), sitting in a flying bathtub – as a clear cultural memory icon, specifically, as a reference to the girl in the red coat from Schindler’s List, who appears as a key figure through whom Oskar Schindler first truly starts to grasp the scale of the Holocaust. Others might not make this mental connection. For those players without this prior memory cultural knowledge, however, the game presents ‘red’ simply as a signal colour. In this scenario, for instance, it indicates which rocks must be targeted to destroy the giant fish in order to rescue the children.

This might take some players only one try. Yet, it might take me 25 tries.

Summarising, My Memory of Us challenges on both a gameplay and content level, and is designed to be variable. Accordingly, the access to the past shaped by the game – if it is indeed perceived as such – occurs in an individualised manner, closely connected to the interactive moments of the medium.

The individual gaming performance of a player influences the outcome even more strongly in the strategy game Through the Darkest of Times, where they are involved in coordinating a resistance collective in Berlin during the 1930s and the Second World War. Even if two players started out with the same character, their decisions during the gameplay, e.g. concerning their group members, their respective activities and the goals that the group sets for itself, will change the actual experience completely. They might outplay a story where the resistance is ‘successful’ and the group survives until the war ends and the Nazi regime is defeated (Figure 3). Here, the game culminates, as illustrated with Figure 3, in a final dialogue sequence that shows all surviving members of the player’s group. Yet, players might also fail; then, they get rewarded by a fictional monument and a file only, documenting their efforts in the civil resistance (Figure 4). Especially in the direct juxtaposition of the screenshots, the message that Through the Darkest of Times ultimately conveys about media of remembrance becomes clear: where direct access to witnesses is no longer possible, media take their place. In the game’s setup, players can trace the fates of individual characters through the simulated missions. Their investment is just as significant. Thus, even the experience of failing in a memory-cultural sense can represent a successful act of remembrance.

Thus, in game settings, players are automatically, though subtly, made aware of their agency: after all, they experience their own interactive involvement as essential to advancing the game's progression and allowing themselves to unfold within the digital space.

In my use of the term ‘interactivity,’ I encompass all four dimensions that Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman introduced in their seminal work on game studies, ‘Rules of Play’. Most importantly for this argument is the dimension of interactivity that extends ‘beyond the object’ and is acted out in the surrounding cultures. Here, interactivity is not limited to a single player experience, nor to the mere handling of the medium “game”. Rather, interactivity beyond the object specifically refers to actions that are, for example, triggered by a gameplay experience but take place outside of the medium, even outside of the digital world. This mode of interactivity explicitly includes cultural negotiations within (gaming) communities.

I believe that the greatest potential for memory cultures lies in this form of interactivity. Namely, when the structures surrounding a game serve as actual mediating spaces for cultural memories, allowing the transfer of interactivity from the playful to a cultural memory context to occur in the same location, and thus, comparatively directly.

The core appeal of video games lies in their ability to make players feel involved in the events unfolding on screen. The sense of agency afforded by games means that players influence the dynamics between themselves and the (historical) setting within the game world. Ultimately, translated into the narrative setting, they experience their own role within the negotiation of the story that enfolds through the gameplay.

As memory media, games have brought these processes of active negotiation into the experiential world of post-generations more strongly than any other form of memory media. In their micro-worlds, they offer exemplary proximity.

In other words, digital games affect the relationality between present and past in ways that other media do not. The game becomes a space where meaning about the past is not simply received but co-constructed. This makes video games a uniquely dynamic medium for engaging with history, but also one that raises critical questions about the boundaries of interactivity, responsibility, and the ethics of historical representation.

Returning to the core argument of this answer, I argue that game settings with their limited yet tangible interactive options can serve as petri dishes or micro-simulations to offer their players experiences of re-enacted post-agency.

Post-agency and Prosthetic Witnessing

With the concept of prosthetic witnessing, I have already attempted, based on four case studies, to trace the specific forms of playful activities through which games can facilitate post-agency. Much like the use of ‘post’ in this response, the term ‘prosthetic’ in Prosthetic Witnessing refers to the fragmentary nature of gameplay processes. Drawing on Alison Landsberg’s Prosthetic Memories, prosthetic witnessing is understood as a mediated process that – like a prosthesis – operates at the intersection of the body and the media environment. It unfolds as a gesturally-simulated, yet simultaneously disruptive and at times painful process, due to its inherent distance.

Beginning with the figure of the historical eyewitness, Prosthetic Witnessing aimed to explore the points of connection through which players, by engaging with a game, enact their own form of witnessing. This was explicitly not about a pseudo-appropriation of the position of historical eyewitnesses. Rather, Prosthetic Witnessing is concerned with tracing already established practices of remembrance that have developed around the figure of the witness. My main argument was that the game worlds I studied simulate many of the actions already associated with historical eyewitnesses.

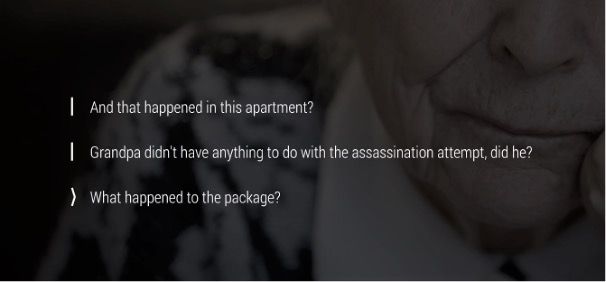

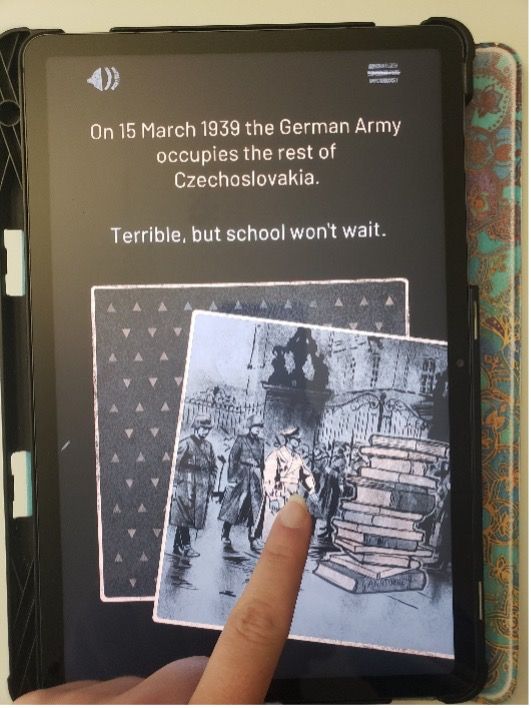

The educational Czech game Attentat 1942 embeds the work of remembrance in the post-Holocaust era in an exemplary and direct way through its gameplay. As players attempt to uncover the story of their grandfather, they examine ego-documents such as his diary, engage in conversations with witnesses, and review film and audio recordings. Naturally, the game mechanics impose certain constraints on these activities, e.g. by limiting conversations with eyewitnesses to multiple-choice-formats for selecting questions and responses. The following screenshot (Figure 5) illustrates one of these conversations during a simulated dialogue with the grandmother, the first witness that the player encounters in Attentat 1942:

While certainly limiting the interactive options, these restrictions also keep the flow of the dialogue going. We never experience moments where we don’t know what to say or what to ask, since there are always offers from which to choose.

The forms of enacted post-agency offered within this game world can, in principle, be transferred directly into the reality that we, as post generations, experience when turning towards cultures of remembrance. Referring to Richardson-Walden’s typologies in her provocation that opened this Dialogue, activating players as memory actors through their own post-agency in relation to this past, might be most easily achieved through digital remembrance games. In this sense – and addressing a second of the posted questions – I argue that the transfer from game-based interactivity to memory cultural post-agency is more easily and directly realised when the player’s position in the game simulates a post-Holocaust context.

Naturally, the game itself does not provide instructions suggesting that the actions it offers also hold relevance beyond its game world. Rather, we are, after all, accustomed to games where individual actions are confined to the logic of the specific game or franchise, for instance, in Mario Kart, dropping bananas on the racetrack to cause accidents is part of the mechanics but has no bearing on real-world driving. Similarly, the context in which Attentat 1942 is played often remains undefined. Returning to Salen & Zimmerman's notion of ‘interactivity beyond the object’, the question remains: is the remembrance-cultural ‘beyond’ too remote?

Based on conversations with various educators during Let’s Remember!, the answer seems to be yes. Even when young visitors come to a memorial site equipped with knowledge of how to explore historical game worlds, this knowledge does not activate itself automatically. Digital remembrance games alone, therefore, do not fully realise the potential of interactive gameplay to foster remembrance-cultural post-agency.

At the same time, many game worlds with historical settings go beyond simulating a post-position, tending to blend out the ‘post’ dimension as much as possible. They often present more problematic forms of agency – such as rescuing eyewitnesses, making decisions on their behalf, and ultimately leading history to a seemingly happy ending. I find such offers still very problematic and therefore consider the interactive potential of games in replicating a single historical position to be rather limited. In fact, this raises the question of whether their portrayal already marks the boundary of interactivity.

Why It’s Not Enough To Offer ‘Interactivity Within Games’ Without a Reference To ‘Beyond’

Cultures of remembrance are always shaped by a reflexive perspective between past and present. Memory cultural significance thus arises when the connection to history is expanded; it always requires the component of ‘beyond.’ At the same time, approaches to digital games as media of remembrance tend to focus too strongly on the purely interactive possibilities within a game world. The ‘beyond’ connections—whether concerning the specific scenario or concerning the scope of actions and their relationship to practices or cultures of remembrance —are still largely neglected. In my opinion, the most fruitful impulses of interactivity do not unfold when viewed solely within the game world itself, but rather in their referentiality to remembrance cultures beyond it. Digital games that see themselves as media of remembrance and are designed as such should therefore include this component of beyond the historical setting; focusing solely on the historical negotiation is not enough.

Thus, in my view, several key factors argue against historical settings in games where players assume a historical role and are not encouraged – within the game structures, its surrounding submenus or a controlled context within which the gameplay takes place – to distance from this role and its perspective. These include,

· firstly, the ‘improper distance’ that rises in relation to both victimhood and perpetration, and

· secondly, the media clash inherent in a format designed with logics of winning and definitive closure. This stands in stark contrast to a history whose traumatic consequences continue to haunt and affect us: one that resists closure and that we quite rightly refuse to lay to rest through our work.

Lilie Chouliaraki argues that when privileged consumers engage via media with victims of structural violence or trauma, ‘improper distance’ occurs. While the consumers may appear to acknowledge the victim’s position, they immediately overwrite it through their own experience as involved witnesses. In this process, the voices of the victims are not truly heard but rather remain silenced, once again instrumentalised as a backdrop against which the Western self can be defined.

This imbalance of power and improper appropriation of the position of another can ultimately be transferred to the historical representation of Nazi crimes or references to the Holocaust in a historical game setting. In the end, we as players are confronted with a game system – that is, a subjective interpretation of the past – and through the act of playing, we are all too often affirmed in a morally positive position, precisely, because we have saved a victim of destroyed the Nazi regime.

Therefore, to perform a historical position in videogames means always to appropriate it in some way. Consequently, any act of participation risks overwriting the historical reality with our own present-day interpretations. The very process of stepping into the past is shaped by contemporary perspectives, assumptions, and desires. Remembrance of the Holocaust then gets commodified, pressed into a structure of resolution, loops, and a clear ending. Put differently, in such moments, we forget the ‘post’-quality of our agency and might perceive it as historical agency.

In contrast, I see an advantage when games make their own limitations – their representation of a micro-excerpt – part of the gameplay itself. This can be achieved, for example, by reducing the narrative scope and gameplay mechanics, as well as by incorporating an inherent reference to remembrance practices beyond the game world. Perhaps surprisingly, I see the impact on memory cultures through interactive gameplay as most effective when the principle of ‘less is more’ is applied.

The Power of Limited Options and Mundane Gestures

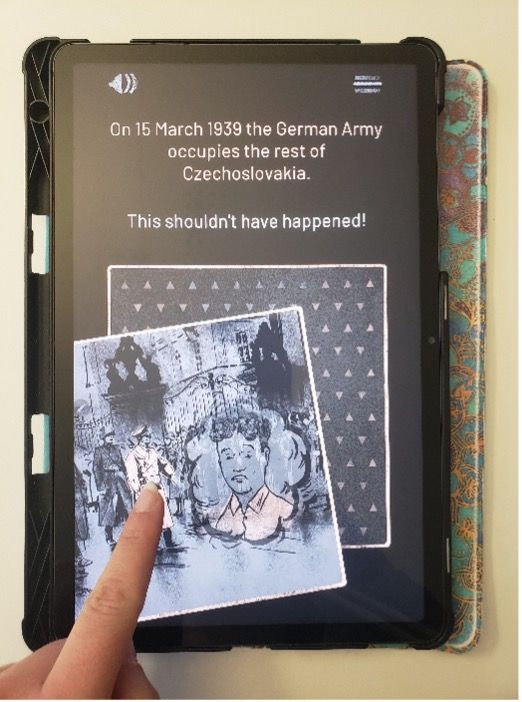

In her provocation piece, Richardson-Walden adopts a critical stance towards the game Train to Sachsenhausen and its limited options of interaction. The game employs mechanisms familiar from popular dating apps like Tinder, with decisions made by swiping left or right.

I would argue, however, that this focus on a single core interactive mechanic actually serves to condense, and thereby intensify, the experience of post-agency.

As shown in the images, players make decisions by swiping cards from a simulated deck in different directions: swiping right or left indicates the different options available. By placing, players choose a specific course for the story, which must then be further shaped with the next decision.

Rather than offering a pseudo-universal systemic response or aspiring to a grand narrative of cultural remembrance, Train to Sachsenhausen pursues a micro-level approach: a small, self-contained moment within the broader historical context, paired with an equally limited scope of interactive engagement.

In Train to Sachsenhausen, the balance between player investment and system mechanics is heavily weighted in favour of the player, while at the same time maintaining a narrative distance from the story being told. We are not tempted to identify with the young student, yet we are drawn in by the constant decisions we have to navigate.

The ‘post-’ or ‘prosthetic’ nature of the scenario, while severely limiting the available choices, makes the opportunity for intervention and the weight of decision-making all the more tangible and relatable. These constrained spaces for action do not diminish the player's experience; rather they heighten the sense of responsibility, making the player more attuned to the significance of their actions within the historical context of the game.

It is precisely this single key mechanic that powerfully highlights the complexity of decision-making through a simple, quite mundane gesture, the game emphasises how even the most routine decisions are laden with meaning. It suggests that important, life-altering choices are not just about grand heroic acts but often emerge from the most basic of actions. Moreover, this familiar gesture, borrowed from the world of media consumption, re-establishes a connection to what lies beyond the game – a very recognisable ‘beyond’.

In my view, then, reducing mechanics and interactive options, can actually encourage critical reflection and awareness of the rupture between the historical events and ourselves, as post-interpreting memory actors. Our scope for action is painfully limited. It is either left or right, yes or no, to stay or to leave.

The interactive choices in the game not only make us aware of our own involvement in the events and our personal agency within the gameplay but also confront us with our own relative position to what unfolds – the post-dimension from which our access to the past arises.

Consequently, I see the potential of playful interactivity expressed most clearly in those game settings where it diverges most significantly from other forms of memory media. Namely, where games confront us with the inter-play of various agencies that shape the individual experience of cultures of remembrance.

(Inter)acting Out post-agency as a System-related Agency Beyond the Individual

Agency in the digital realm is always ambiguous, as it is shaped by both individual decisions and technical forces. With algorithms that inform an attention economy, platforms like TikTok, X or Instagram are designed to steer user actions by delivering personalised content that captures their interest and maximises engagement. This technical agency is reinforced by algorithmic systems that analyse and predict user behaviour, aiming to capture their attention. The control that digital systems exert over users’ decisions is often perceived as invisible, as it operates in the background, giving the impression that users are acting ‘freely’. In reality, however, their options are heavily shaped by the structures of the platforms which in turn are ever shifting, holding an ‘on the fly’-quality, as Andrew Hoskins argues. Thus, agency in the digital space becomes a complex interplay of autonomy and technological influence, where the boundaries between free will and algorithmic control are blurred.

Summarising, here post-agency refers to the ongoing process of human-system-interaction that shapes video games. I, as the individual player, may have a certain agency which I seek to express in my gameplay. However, as the player, I am only part of the complex structure that underlies interactions in video games. The systematic mechanisms through which my actions are translated and interpreted into the digital realm hold an agency of their own.

Souvik Mukherjee stresses this interconnection of game system and player most strongly when he argues that playing a game is an act of agency and becoming. Drawing on Gille Deleuze’s philosophical understanding of agency, Mukherjee argues in his monograph Video Games and Story Telling that ‘[…d]uring gameplay, the machine can also be considered a player and the human player a part of a certain algorithmic sequence.’ Thereby, post-agency in this perspective, refers to the fact that there is agency beyond my own at play, figuratively as well as literally. Games bring forth a kind of agency that emerges through the interplay of multiple actors, human and system forces, alike.

An installation from my current work context, at the Zeppelin Museum, in my view, vividly exemplifies this understanding of post-agency. Even though it is far removed from the context of Holocaust remembrance, it is intended here to illustrate the interplay of various agencies that also influence digital cultures of remembrance:

The game installation Where Do the Ants Go by Indian artist Afrah Shafiq simulates an ant colony. According to the artist, the simulation is programmed so that the ants search for the shortest route from a food source to their nest. However, visitors ‘produce’ the food sources themselves by entering their emotions via a keyboard – without knowing what emotional input the ants have already received from previous participants. Depending on the type of ‘emotional nourishment’ the colony is fed, it may become imbalanced. This imbalance, in turn, can lead to the colony’s destruction, either by flooding or fire – an outcome that users can no longer influence.

Even when visitors intend to strengthen the colony with positive emotions, their intervention could still destabilise the overall system. These processes are commented on by the ant queen (Figure 8), who directly addresses the visitors, repeatedly drawing attention to the artificial nature of the scenario. In doing so, she exposes human hubris and our ambivalent relationship with technology, while also questioning the extent to which natural structures can truly be transferred into digital spaces. The system’s agency thus becomes increasingly opaque.

The key moment of interactive participation in this installation lies precisely in the rupture between player agency and system agency: the realisation that one’s own choices may result in consequences beyond one’s intentions. At the same time, the installation prompts a deeper question: what kind of systems are we actually engaging with? Are we aware of how our actualised agency and our interactive engagement actually influences the output?

The installation Where Do the Ants Go was part of the exhibition Choose Your Player at the Zeppelin Museum on Lake Constance. In this context, the relationship between games and museums was made explicit, directly linking interactive experiences with institutional spaces of cultural memory. This brings me to my final point: so far, the idea of ‘beyond’ has remained somewhat vague. However, perhaps shaping this ‘interactivity beyond the object’ more concretely in the context of digital cultures of remembrance, might be simpler than we think. Rather, I’d argue the quality of interactive participation appears to be a productive means of re-entering and making accessible already established spaces of cultural remembrance. I will explore this idea further in the following section.

There and Back Again – The Interconnection of Games and Educational Spaces

Museum spaces, however differently they may be designed, are, much like video games, defined by structured frameworks of interaction: we read texts, we interact with objects, and acquire knowledge through movement within the space. As visitors, we possess the agency to determine our direction of movement and choose the information with which we engage.

What may unconsciously feel like a passive act of reception – merely absorbing curated knowledge – is, in fact, a process of reciprocal agency. As visitors, we navigate the museum spaces, actively shaping our experience. Yet, at times, perhaps because we feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information – we may overlook or even relinquish our own sense of agency.

The exhibition Choose your Player was entirely dedicated to the cultural phenomenon of (digital) games and playing – featuring numerous gaming stations within the museum space. As a result, visitors gained a new kind of access to the museum itself. Watching them during their visit, we, as the staff, could perceive how they constantly renegotiated their idea of what constitutes an exhibit and how one is allowed to interact with it. Does an object belong to the museum’s furnishings, or is it part of an artistic installation? How much time am I allowed to spend playing? It was at times even moving to see how especially younger visitors, after approaching the exhibition only hesitantly at first, gradually found an increasingly natural form of engagement with the games.

These reflections were further reinforced by offering visitors the opportunity to embark on their own RPG adventure within the exhibition spaces – an experience specially developed in collaboration with the studio Orkenspalter. Guided by the museum’s so called debatorial® - a digital platform that continuously reflects on the content of temporary exhibitions and encourages discourse and exchange on the exhibited themes. Visitors could use either their smartphones or traditional brochures available on-site to identify additional parts of the exhibition as game stations. For those who chose not to participate, these elements remained purely aesthetic design features. As a result, visitors emerging from the solo RPG-adventure engaged with the same exhibition elements in a noticeably different way compared to those who only interacted with the clearly designated game stations.

Even more crucial to my argument, however, was the extent to which this playful activation extended beyond the moment of play itself. Carried by a sense of ‘what's next?’, visitors moved from these active gaming experiences further into the exhibition. Not only did their willingness to engage with other stations – investing time and energy –continue to grow, but their movement through the museum space also became more purposeful, self-directed, and exploratory.

In the shared space of the exhibition, it was possible to establish a dialogical relationship between game structures and mediation structures. While the mediation context broadened the perspective on games as exhibition objects, this interaction facilitated an activated access to the museum space, with the personal agency and responsibility entrusted to the visitors.

However, in my view, this new perspective on the actual space, the transfer into our analogue dimension in which we maintain presence through our bodies and movements, would be lost if it were completely transferred into the digital realm and incorporated into a game world. The habituation effect is too strong, as immersive worlds on the screen seem to possess their own magic circle. The idea of transferring museums into digital game worlds, as attempted with Voices of the Forgotten, may initially seem appealing and straightforward. However, this logic ultimately falls short. What is missing is the facet of ‘interactivity beyond the object,’ which emerges in the actual spatial encounter between game and museum, accompanied by the corresponding curatorial guidance. Ideally, on-site gaming experiences inspire visitors to perceive the museum itself as a space of their own post-agency, encouraging them to engage with its content in a more action-aware, perhaps even more self-confident, way.

Much like the literary figure Bilbo Baggins from The Hobbit, who subtitled his adventures ‘There and Back Again’, the value of playful interactivity for cultures of remembrance lies in its function as a condensed space of experience with the past; a space that allows us to gain reflexive distance from our memory-cultural practices. Yet it is equally important to return from these spaces to the familiar analogue settings of mediation, bringing with us the experiences of our own participation and sense of enacted agency, both in terms of media technology and cultures of remembrance. In this way, the transformative potential of our post-agency, as responsible actors within cultures of remembrance, may be most fruitfully activated.

Let’s Build More Dialogical Spaces between Game and Educational Spaces!

My reflections in response to the offered provocation have led me to the following conclusions:

· Firstly, in my view, engaging with interactivity shifts the focus in the right direction: towards the post-agency we hold in relation to cultures of remembrance, which is expressed through our participatory actions – making it visible and, consequently, open to reflection.

· Secondly, if we continue to focus primarily on questions of ‘interactivity with(in) the object,’ we risk neglecting the very sphere in which the interactive affordances of digital games could be most fruitful for remembrance practices – namely, the subsequent ‘interactivity beyond the object’ limited, yet clearly defined, game actions enter into a fruitful dialogue with the practices of living cultures (of remembrance).

· Thirdly, it is crucial to break open the closed – or at least seemingly closed –spheres of gaming culture and remembrance culture. In this process, I consider the dimension of space to be an important analogue anchor zone, where the dialogical encounter between interactive gaming and remembrance practices can truly unfold, and where post-agency can be meaningfully activated.

At the same time, I would like to explicitly highlight the term 'post-agency' not only as a call for much-needed participation but also as an expression of my personal concern that, through our current consumption habits and collective political decisions, we are simultaneously participating in systems that could, sooner or later, deprive us of our agency. In this sense, post-agency also carries a dystopian undertone, pointing to the very real possibility that we may soon enter a phase in which our capacity to act is increasingly diminished.

For me, the key questions at present, stemming from interactivity and post-agency at the intersection of games and the discourse on cultural memory, are:

· How can we create productive connections between games and educational spaces that invite reflections on the own post-agency?

· How can we introduce fruitful moments of rupture and irritation where a feeling of discomfort makes of aware of the vulnerability of our post-agency?

· What other dialogical spaces might we create where interactivity ‘with(in) the object’ and ‘beyond the object’ can be experienced?

· Can this happen purely on a structural level, or does it always require human agents to facilitate the transfer process?

· And how might we connect memory cultures even more closely with civic education so that we don’t find ourselves soon in a ‘system after agency’?

Author Bio: Dr. Tabea Widmann

Dr. Tabea Widmann is responsible for digital mediation and format development at the Zeppelin Museum. Previously, as project lead at the Foundation for Digital Games Culture, she headed pilot projects at the interface of games and memory cultures as well as foreign policy. Her dissertation, "The Game is the Memory," explored games as memory media and forms of mediatised witnessing. Her research and work focuses on digital (memory) cultures and social transformations through digital technologies.