Defining Holocaust Games

In our work at Painbucket Games, and for the sake of this dialogue, we define a Holocaust game as an interactive digital experience that engages with the systematic persecution and genocide of Jews and other targeted groups by the Nazi regime between 1933-1945 following Chapman and Linderoth 2015 and Pfister 2020.

Holocaust games should meet at least one of the following criteria:

- Victim-centered perspective: The game presents experiences, narratives, or choices from the perspective of Holocaust victims or survivors, particularly Jewish individuals and communities who were the primary targets of genocide. Games like Luc Bernard's The Light in the Darkness (2023) exemplify this approach.

- Explicit representation of persecution: The game engages with the processes of discrimination, dehumanization, deportation, or extermination rather than merely alluding to them as background context (Kansteiner 2017).

- Memorial intention: The game is explicitly created with the intention to educate, commemorate, or preserve memory of the Holocaust, with historical accuracy and respect for victims as primary design considerations. Projects like Witness: Auschwitz (2018) by 101% or Marion's Journey by Gathering the Voices exemplify this approach.

Not all games set during the Nazi era qualify as Holocaust games. For example, games that focus primarily on military combat (like many World War II shooters) or resistance movements without directly engaging with Jewish persecution would better be categorized as "Nazi-era games" or "World War II games" rather than Holocaust games specifically (Pötzsch and Šisler 2019).

Our games at Paintbucket occupy various positions on this spectrum. While Through the Darkest of Times and The Darkest Files deal with Nazi persecution and include Holocaust content, they employ what might be called “moments of distancing" - positioning players as witnesses, investigators, or resisters rather than direct victims of the Holocaust. This approach represents one ethical framework for creating games that engage with Holocaust memory while respecting certain boundaries related to the direct simulation of genocide (Walden 2021).

Creating a Holocaust game carries particular ethical responsibilities and design challenges distinct from creating games that merely use the Nazi era as a historical backdrop. The fact that so few games directly engage with victim experiences reflects both ongoing cultural hesitancy about Holocaust representation in interactive media and the genuine design challenges of respectfully representing genocide in a playable format.

From Niche Interest to Recognised Medium

Through my experiences developing multiple titles that include Holocaust representation, I've witnessed firsthand how institutional skepticism and cultural rejection have given way to genuine acceptance, sophisticated game design approaches, and recognition of games as vital tools for Holocaust memory in the digital age.

When we started developing Through the Darkest of Times in 2017, we faced a climate that viewed Holocaust-themed games with suspicion at best and outrage at worst (Kreienbrink 2017) . Today, as we released The Darkest Files in 2025, the landscape has transformed remarkably (Huberts 2025) . This evolution hasn't happened by chance but through deliberate efforts by developers, historians, educators, and cultural institutions to establish games as legitimate vehicles for Holocaust memory and education.

When we started to develop Through the Darkest of Times we had modest expectations. We initially targeted a very specific audience: historians who were already gamers. This demographic seemed the only viable audience for a game dealing with civilian resistance to Nazi oppression, as we anticipated that most mainstream players (and the connected press) would reject the premise outright. The prevailing question at that time was whether a game with this subject matter could ever be "fun" – a misguided but common framework for evaluating all games regardless of their purpose.

This concern about entertainment value overshadowed the medium's potential for education and commemoration. As Wulf Kansteiner is quoted in the provocation text, by avoiding the medium due to fears of trivialising the Holocaust, we risked ‘leaving the field wide open to dubious right-wing concoctions’ – precisely what happened with early examples like KZ Manager.

When we began developing Through the Darkest of Times, we didn't even approach publishers initially, as we didn't expect any would be interested in such challenging subject matter. To our surprise, publisher THQ Nordic offered to publish the game in 2018, later transferring it to their indie game division HandyGames. Even in our early demos, we operated with extreme caution – omitting swastikas despite their historical accuracy (prior to Germany lifting this restriction in games) and carefully framing violence to avoid any suggestion of glorification.

Today, just a few years later, our newest title The Darkest Files has attracted a much broader audience. Players approach it primarily as an investigation and courtroom game, with the historical setting as a compelling backdrop rather than a deterrent. The game is evaluated first on its merits as a game, while still being recognized for its historical significance – representing genuine progress in how Holocaust-themed games are perceived and received.

The German Controversy Over Nazi Symbols in Games: A Turning Point

The entrenched resistance to Holocaust-themed games became starkly evident in August 2018, midway through our development of Through the Darkest of Times. When the German age ratings board for games (USK) announced they would begin evaluating games with Nazi symbols like swastikas for age ratings (Berliner Morgenpost 2018) -potentially allowing such symbols in games that qualified for the ‘social adequacy’ exception – the public response revealed just how controversial games addressing this history remained.

Through the Darkest of Times became the first German game to benefit from this policy change, allowing us to include historically accurate Nazi symbols in our Gamescom demo. The backlash was immediate and came from various quarters. The Israeli Ambassador to Germany expressed shock on Twitter, writing: ‘I am shocked that a Berlin company was allowed to use the abhorrent and offensive swastika in a new computer game. This terrible symbol should have no place in Germany, especially not in the games of youth’ (Berliner Morgenpost 2018).

Even more concerning was the response from government officials. Federal Family Minister Franziska Giffey (SPD) warned that ‘You don't play with swastikas’ (Berliner Morgenpost 2018) . Especially in Germany, we must always be aware of our special historical responsibility.’ Elisabeth Winkelmeier-Becker, legal policy spokesperson for the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, claimed computer games were unsuitable for ‘appropriately dealing with the historical injustice of National Socialism’ (Berliner Morgenpost 2018).

The German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) went further, criticising the process itself: ‘the change secretly brought about during the parliamentary summer break, without involving parliaments and social groups, must not be accepted. We demand the withdrawal of the USK decision’ (Buntenbach 2018).

Perhaps most revealing was the response from Lothar Hay, Chairman of the Media Council of the Media Authority Hamburg/Schleswig-Holstein, who flatly stated that ‘the decision of the Entertainment Software Self-Regulation (USK) to release computer games with swastikas and other symbols of unconstitutional organizations is wrong’ (Hay 2018). He explicitly rejected the comparison between games and films, arguing that ‘the effect of violence in games is considerably more problematic’ due to interactivity and reward systems.

These reactions demonstrated that even in 2018, computer games were still viewed with fundamental suspicion as a medium for addressing the Nazi era. Critics weren't merely concerned about specific implementation details; they questioned whether games as a medium could ever appropriately handle this history. The prevailing assumption was that interactivity itself was inherently problematic when dealing with National Socialism.

We found ourselves defending not just our specific game but the legitimacy of games as a medium for historical education. As Through the Darkest of Times’s game designer, I responded to critics by highlighting their outdated understanding of games: ‘there are young people who no longer watch films. These young people learn their historical image only from computer games - and in this historical image there should be no Nazis? No Second World War, no Holocaust, no antisemitism? I consider that much more dangerous’ (Berliner Morgenpost 2018).

This controversy represented a critical turning point. While met with resistance, the decision to allow Nazi symbols in games acknowledged the potential cultural and educational value of games alongside film and other art forms. It marked a step toward recognising games as a legitimate medium for engaging with this difficult history, though the strong pushback showed just how far we still had to go.

From Controversy to Nuanced Dialogue

What began as a contentious debate eventually evolved into a more productive conversation about the role of games in Holocaust education and remembrance. Following the initial wave of criticism, more thoughtful voices emerged to challenge the blanket dismissal of games as inappropriate vehicles for engaging with Nazi history.

Israeli novelist and game designer Assaf Gavron published a compelling counterargument in Die Welt (Gavron 2018), questioning the logic behind removing Nazi symbols from historical games. ‘If we had used flags other than the Israeli and Palestinian ones for 'Peacemaker,' altered the uniforms of the Israeli Defense Forces, and removed the keffiyehs from the heads of Palestinian fighters—how could we ever have achieved the goal of the game, which was to bring young people closer to the complexity of the Middle East conflict’," he wrote, drawing comparisons with his own game.

Gavron (2018) directly addressed the concerns of Family Minister Giffey, flipping her assertion that ‘you don't play with swastikas!’ on its head. ‘On the contrary: we should play with swastikas. We should not hide them, precisely because they once existed and actually stood for something. We need to be aware of this. Taking responsibility in this context means telling the past exactly as it happened, rather than fictionalising it.’

His perspective as an Israeli writer carried particular weight, challenging the assumption that prohibition was the only respectful approach to Holocaust remembrance. Instead, he argued that historical authenticity in games could be a powerful tool against rising right-wing extremism: ‘A video game in which Nazis are fought, in which history is told as it took place, is certainly a useful tool to put these groups in their place and to thwart their desire to lead us back to the darkest times in world history.’

Perhaps most remarkably, Family Minister Franziska Giffey herself demonstrated how rapidly perspectives could evolve when exposed to the actual work rather than abstract concerns. The very same day her sharp criticism was reported across all media outlets, she visited the Gamescom exhibition where I personally demonstrated Through the Darkest of Times to her. That evening, she posted on social media after speaking with our team(Giffey 2018). While maintaining her general position against the use of Nazi symbols as gameplay elements, she acknowledged that in exceptional cases – similar to films like Schindler's List – such symbols could be permitted when the context justifies it. She recognised that Through the Darkest of Times represented one of these justified exceptions. This nuanced evolution in her stance highlighted how direct engagement with thoughtfully designed games could lead even skeptical critics to recognise their potential value in remembrance culture.

Similarly telling was the response from union leader Annelie Buntenbach. After her initial criticism and my reply, she invited us to present the game to a committee of union representatives. While there was no public statement retracting the original criticism, I view the fact that no further objections came from the unions following this meeting as a sign that a process of reconsideration had begun. This silence suggested a growing recognition that games like Through the Darkest of Times could indeed have an important place in cultural memory and education about the Holocaust.

In my own response to Lothar Hay's critique (Friedrich 2018), I highlighted how the medium of games was following a similar trajectory to comic books, for example Art Spiegelman’s Maus (Leventhal 1995) – another format once deemed inappropriate for Holocaust representation. I said, ‘just as you deny that computer games can deal responsibly with this topic today, back then there was a public prosecutor's office convinced that comic books could not deal responsibly with the topic of National Socialism (Der SPIEGEL 1996). Nobody believes that anymore.’

I emphasised the generational aspect of media consumption: ‘If my parents were educated about the Shoah and National Socialism by a TV series, and I was educated by a comic book, then perhaps a computer game will one day play this role for my son’. This intergenerational perspective was aimed to reframe games not as trivialising Holocaust memory, but as extending it to new audiences in forms they would meaningfully engage with.

What emerged from this debate was a more nuanced understanding of how games might appropriately engage with Holocaust history in Germany. Rather than categorical rejection based on the medium itself, critics and supporters began examining specific approaches, mechanics, and contexts that would respect the historical gravity while leveraging games' unique educational potential.

This shift from whether games should address the Holocaust to how they should do so marked an important evolution. It created space for more productive collaboration between game developers and Holocaust educators, laying groundwork for the wider acceptance of thoughtfully designed Holocaust-themed games we see today. The controversy, painful as it was, ultimately helped establish more sophisticated criteria for evaluating such games, moving beyond simplistic rejections to substantive engagement with their educational and commemorative potential.

Evolving Game Design for Effective Holocaust Representation

Through developing games about the Holocaust and Nazi era since 2017 – from our resistance simulation Through the Darkest of Times to our prosecutorial investigation The Darkest Files, alongside commissioned memorial projects like Remember: The Children of Bullenhuser Damm and Forced Abroad – we've gained concrete insights into effective approaches for Holocaust representation in games. This period has also seen important contributions from other developers, including Charles Games' documentary-based Attentat 1942 and interactive narrative Train to Sachsenhausen, as well as Luc Bernard's victim-centered The Light in the Darkness. Each of these projects has pioneered different approaches to Holocaust representation, and studying their innovations alongside our own experimentation has accelerated our collective understanding of effective design strategies for this sensitive subject matter.

One key finding from our practice concerns player positioning. We've found that post-Holocaust investigative roles often work better than placing players directly in victim or perpetrator positions, particularly for a broad audience outside of educational contexts. This creates a more accessible entry point while still enabling meaningful engagement with history.

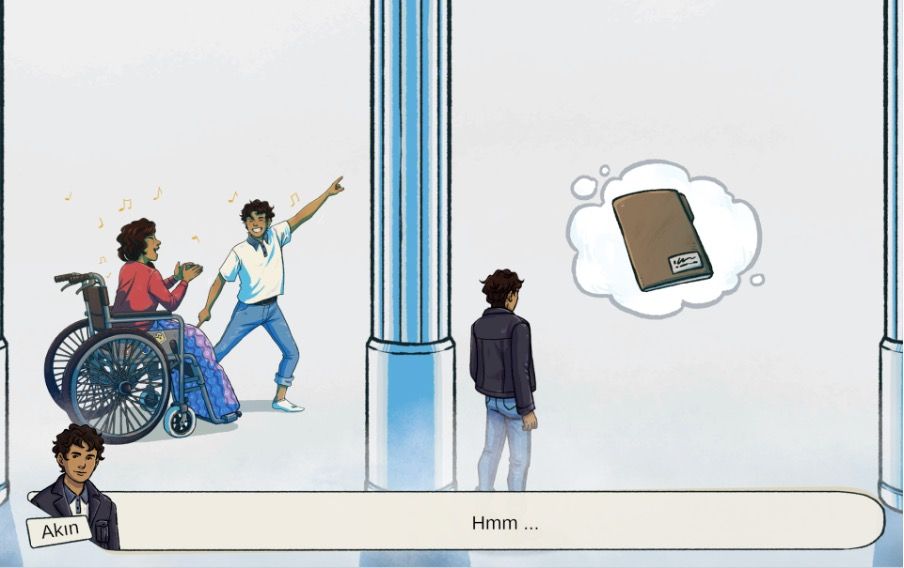

In The Darkest Files, we substantially evolved our approach to Holocaust representation. For example, unlike the multiple-choice dialogue system of Through the Darkest of Times, which offered limited interaction options when encountering sensitive situations, The Darkest Files implements almost free-roaming gameplay during witness testimony exploration. Players can physically navigate remembered spaces, examine objects, and piece together evidence at their own pace. We found this approach creates deeper engagement without trivialising historical events.

These interview sequences evolved from techniques we first implemented in Through the Darkest of Times, where players could for example talk to an Auschwitz survivor through structured dialogue trees.

Figure 2: interview sequence in Through the Darkest of Times (public playthrough 4:00:47 - 4:04:31 showing the limited interactivity)

Our approach to testimony evolved between Through the Darkest of Times and The Darkest Files, particularly in how we staged different types of witness accounts and calibrated player agency.

In Through the Darkest of Times, when players encounter Holocaust survivors, the testimony sequences position them as passive listeners receiving traumatic accounts, with minimal interaction options emphasising respectful witnessing over active asking.

In contrast, The Darkest Files expands player agency through its “immersive mode” which allows players to freely navigate the recounted memories surrounding them.

The fact that the person you talk to might be a perpetrator in The Darkest Files means everyone could be an unreliable narrator, so accounts must be actively scrutinised rather than passively accepted. Players must cross-reference their statements against documented evidence, identify inconsistencies, and challenge fabrications.

The "immersive mode" in The Darkest Files, as we internally called the sequences when players are experiencing the narration of a witness, is significantly more interactive and better leverages the medium's strengths, allowing players to explore witness testimonies – making distant historical events more immediate without requiring players to directly act within these traumatic narratives.

Figure 3: In The Darkest File’s “Immersive Mode” players explore the testimony of witnesses (public playthrough video starting 1:03:23 - 1:13:43)

We also incorporated document-based investigation, allowing players to reconstruct historical events themselves – deliberately permitting them to make mistakes in their interpretations. The final confrontation with the actual historical case serves as a powerful corrective moment, reinforcing factual understanding.

Figure 4: In the Darkest File’s document mode, players are exploring (simplified) historical documents to reconstruct a crime - public playthrough 2:31:28 - 2:37:05 - player sorts documents and marks them to form their theory for court.

These design solutions address an initial concern we had with post-Holocaust framing: that players might feel too removed from historical events. Our mechanics aim to create meaningful connections while maintaining appropriate distance, respecting both historical accuracy and players' emotional boundaries.

In Remember. The Children of Bullenhuser Damm, we further refined our approach by developing the "remembrance room" as a bridge connecting players to historical events. This mechanism feeds fictional player experiences with factual information while allowing characters to enter narrative spaces. Players can experience these stories interactively without needing to generate the empathy required to imagine themselves directly in traumatic situations.

This distinction is crucial because research has demonstrated fundamental differences in how we engage with so-called passive versus interactive media. From our own experience in designing emotional games (Friedrich 2012) and backed by a 2016 study on ‘observers versus agents’ (Dohyun Ahn and Dong-Hee Shin 2016), when players become agents who must make decisions, their empathic connection can be compromised by the cognitive demands of gameplay. Perhaps feeling frustration at a challenging puzzle when the narrative demands sadness or focusing on optimising outcomes rather than emotional understanding. Film viewers, as passive observers, face no such cognitive conflicts and can fully immerse themselves in empathic responses to protagonists.

We continue wrestling with the challenge of Jewish representation highlighted in the provocation piece. A central issue we face as developers is how to present victim perspectives while maintaining meaningful player agency. We believe this is possible – The Light in the Darkness demonstrates one approach to this challenge.

Games can create an "illusion of choice" in seemingly hopeless situations, which can actually amplify the sense of powerlessness. These ludo-narrative techniques are well-established and frequently employed in emotional games outside Holocaust contexts (Sweeting 2018). When players exhaust every possible option only to find no escape, the experience can be more powerful than a non-interactive portrayal of the same situation (Friedrich 2012).

As developers, we currently face practical representation challenges. We tend toward abstraction in our visual approach because we're concerned about creating an ‘uncanny valley’ effect specifically when depicting the Shoah. Photorealistic representations of atrocities risk trivialising them even when perfectly executed.

It's notable that even The Light in the Darkness, groundbreaking as it is, ends before the gates of Auschwitz, not crossing that threshold. However, I'm convinced we will see games in the coming years that do venture further, attempting to represent concentration camp experiences. As a development community working with Holocaust institutions, we should proactively establish guidelines and principles for constructive approaches to such representations, rather than simply reacting to controversial releases when they inevitably arrive.

Interactive Literature vs. Computer Games: Navigating Systemic Gameplay in Holocaust Memory

The provocation piece raises a challenging question that resonates deeply with me as a game designer: ‘would the majority of Holocaust-related “games” currently available be better described as interactive literature? Have we actually created any computer games about the Holocaust yet?’ This is a valid concern that deserves serious discussion, particularly between game designers and Holocaust memorial institutions.

The distinction between interactive literature and true computer games lies primarily in systemic gameplay and there's a noticeable difference between our self-produced commercial titles (Through the Darkest of Times and The Darkest Files) and our commissioned memorial site projects in terms of systemic gameplay. Our commercial games incorporate more system-based mechanics, while our memorial projects lean more toward interactive storytelling. This isn't accidental. Creating meaningful systems-based games requires greater freedom in what can be displayed and what potential outcomes might occur, which can create tension with memorial institutions' need for historical accuracy and respectful representation.

However, for games to reach their full potential as a medium for Holocaust memory, they need these systems to create significant, meaningful choices. A purely narrative choice gains tremendous power when it produces not just a narrative consequence but also a systemic one. When players see how their decisions ripple through game systems, affecting multiple dimensions of gameplay, the emotional and intellectual impact is magnified.

Consider a simple example from game design: in a game where a character begs for money, the player's decision to give carries entirely different weight depending on whether money functions as a game system. If money is a limited resource that affects what players can do later – perhaps preventing the purchase of items needed for survival – the act of giving becomes a genuine sacrifice with systemic consequences. Without this systemic dimension, the choice becomes primarily symbolic, losing much of its emotional force.

Systemic gameplay allows for exponentially more choices and outcomes than designers can pre-design, making games uniquely powerful for exploring complex ethical situations. Yet implementing such systems in Holocaust contexts requires extraordinary sensitivity. How do we create meaningful systems that respect historical experiences without trivialising suffering? How do we build mechanics that allow for player agency while acknowledging the often severely limited choices available to Holocaust victims?

This tension between systemic gameplay and respectful representation explains why many Holocaust "games" remain closer to interactive literature than true games. As a game designer working in this space, I believe we need continued dialogue between developers and memorial institutions to explore how we might thoughtfully incorporate more systemic elements while maintaining appropriate boundaries and respect for history.

The Evolution of Holocaust Games and Expert Perspectives

The controversy surrounding Through the Darkest of Times in 2018 highlighted a pivotal moment in the relationship between games and Holocaust remembrance. This wasn't just about one game, it represented a broader societal reckoning with whether computer games could respectfully address such sensitive historical material. The critical reactions from across the political spectrum, from Israel's ambassador to the chair of Germany's Media Council, reflected deeply held concerns about trivialisation and the appropriateness of the medium itself.

Against this backdrop of skepticism, a remarkable shift has occurred in just a few years. Holocaust remembrance institutions have moved from rejecting games as inappropriate to actively commissioning them. As the provocation notes, The National Holocaust Centre (UK) now confidently describes its Journey app as a ‘game’ rather than an ‘interactive story’. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust Centre of New Zealand, and other institutions have moved from reluctant acknowledgment of games to recognising their educational potential. In Germany, Holocaust organisations worldwide increasingly collaborate with game developers.

What explains this evolution? Several factors have contributed:

· First, the aging of Holocaust survivors has pushed institutions to seek new ways to engage younger generations. While developers once faced outright rejection of interactive approaches, many institutions now recognise games' potential to reach digital-native audiences, particularly as firsthand witnesses diminish.

· Second, persistent developers like Luc Bernard, ourselves, and others have demonstrated that games could handle Holocaust content with appropriate sensitivity. Early projects helped establish a baseline of respectful representation, creating precedents that institutions could reference when evaluating new proposals.

· Third, the perception of games as a medium has matured. Games are increasingly recognised as cultural artefacts capable of serious artistic and educational expression rather than mere entertainment. This shift is evident in the growing academic literature on games in Holocaust education and exhibitions like the Imperial War Museum's War Games (2022), which explicitly addressed the relationship between games and historical conflict.

· Fourth, Holocaust remembrance organisations are increasingly integrated digital media experts into their teams. The hiring of specialists who understand both Holocaust memory and digital media has bridged previous knowledge gaps and facilitated more informed assessments of games' potential.

Perhaps most significantly, memorial institutions have evolved from asking "whether games should represent the Holocaust" to "how they might do so appropriately." This hasn't eliminated concerns about interactivity and representation – these remain vital considerations – but it has shifted the nature of the conversation toward collaborative problem-solving rather than categorical rejection.

The initial reaction to Through the Darkest of Times illustrates how expert attitudes have evolved. When Family Minister Franziska Giffey initially declared that ‘you don’t play with swastikas’, she reflected a widespread view of games as fundamentally incompatible with serious Holocaust memory. Yet after experiencing our game at Gamescom, she modified her position, acknowledging that in certain contexts, such representations could contribute legitimately to Germany's culture of remembrance. This shift – from abstract rejection to engagement with specific content – epitomises the broader evolution in expert thinking.

Today, the relationship between memorial institutions and game developers has evolved into a more mature partnership based on mutual respect and shared goals. While tensions certainly remain regarding representation and interactivity, these are increasingly addressed through collaboration rather than dismissal. This evolution doesn't mean all concerns have been resolved, indeed, important questions about appropriate interactivity, victim representation, and educational impact remain active areas of discussion. But the groundwork for productive dialogue has been established through years of careful engagement from both sides.

The most promising development may be the emergence of collaborative development processes that bring Holocaust experts and game designers together from the beginning. Rather than developers creating games in isolation for later evaluation, institutions like the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres participated in a co-creation process that integrated historical expertise and game design knowledge throughout development. The Alfred Landecker Foundation exemplifies this approach, having both supported the development of Remember: The Children of Bullenhuser Damm and the upcoming Connective Holocaust Commemoration Expo. The Expo represents exactly the kind of collaborative space needed to advance Holocaust representation in games: a forum where memorial institutions, historians, educators, and game developers can exchange ideas, establish best practices, and forge partnerships that respect both historical integrity and the unique capabilities of interactive media.

The Evolution of Critical Reception and Game Design in Holocaust Games

The evolution of critical reception provides another window into changing attitudes. When Through the Darkest of Times was released, reviews often praised it as "important" rather than "good" – suggesting that its historical significance outweighed its merits as a game. This framing implicitly reinforced the notion that Holocaust games occupied a separate category, to be judged by different standards than "real" games.

As German gaming magazine GameStar wrote in their review of Through the Darkest of Times: ‘the audiovisually coherently designed resistance manager is not a perfect game, but an important one. More relevant now than ever’. This backhanded compliment typified the reception – acknowledging the game's significance while subtly questioning its legitimacy as entertainment.

By contrast, reviews of The Darkest Files have engaged more substantially with its game mechanics, interface design, and player experience – treating it as a game and a historical document. Critics evaluate its investigation and courtroom mechanics on their own merits, analysing how effectively they function as gameplay systems while also considering how they convey historical understanding.

This shift in critical reception isn't merely semantic – it represents genuine progress in how games addressing historical trauma are conceptualised and evaluated. No longer segregated as a "serious game" to be praised for its intentions rather than its execution, The Darkest Files is a game about the Holocaust that is held to the same standards of design excellence as games in other genres.

This evolution in critical reception partly reflects our own growth as developers. When creating Through the Darkest of Times, we were pioneering largely uncharted territory, with few models for how game mechanics might respectfully engage with Holocaust history. The result combined simple resource-management gameplay with narrative sequences, maintaining clear boundaries between "playable" and "unplayable" elements of the story.

With The Darkest Files, we've developed more sophisticated mechanics that integrate gameplay and historical content more seamlessly. The investigation and courtroom mechanics emerge organically from the historical subject matter, allowing players to engage directly with historical documents, testimony, and evidence without feeling that they're "playing with" history inappropriately.

The Darkest Files represents a significant advancement in systemic gameplay compared to our earlier work. As developers, we felt less constrained in our design approach and more confident in exploring interactive possibilities after the reception of Through the Darkest of Times. This evolution is evident in the game's richer systems -from the document analysis mechanics to the evidence-building framework - where player choices have more complex ripple effects throughout the gameplay experience.

The game's presentation also contributes significantly to its effectiveness. While far from AAA production values, The Darkest Files offers fully navigable 3D environments and professional voice acting that meaningfully enhance player engagement. This more immersive presentation helps players connect with the historical material on multiple sensory levels. Players become absorbed in the investigative gameplay first and foremost, with historical learning occurring almost as a side effect, precisely the kind of organic educational experience that games are uniquely positioned to deliver.

This level of quality and innovation came with substantial costs. The development of The Darkest Files from concept to release spanned more than four years and required five times the budget of Through the Darkest of Times. Such extended development timelines remain rare in Holocaust-themed games, where funding and timing constraints often limit scope and ambition. Yet this investment of time and resources proved crucial to the project's success.

The extended development allowed us to course-correct when necessary, prototype extensively, gather meaningful player feedback, and ultimately pursue a fundamentally different direction than originally planned. Our initial concept for The Darkest Files was much closer to Through the Darkest of Times in mechanics, relying primarily on strategy elements and visual novel-style interactions. Through iterative testing, we discovered this approach wasn't best suited for immersing players in prosecutorial investigation. The freedom to redirect our efforts toward a more exploration-based design created a substantially stronger experience.

This development trajectory mirrors how many celebrated games in other genres have evolved – through patient iteration and the willingness to abandon initial concepts when better approaches emerge. The mainstream games industry understands this principle well, but it has rarely been applied to Holocaust-themed projects due to funding limitations. Our experience demonstrates that allowing sufficient time for experimentation and refinement can dramatically improve the quality and impact of Holocaust games.

We've paid particular attention to creating mechanics that serve both gameplay and historical education simultaneously. The document analysis system, for example, teaches players about the bureaucratic nature of Nazi crimes while also functioning as an engaging puzzle mechanic. The testimony exploration segments combine atmospheric storytelling with investigative gameplay, allowing players to piece together narratives while exploring historically accurate environments.

Our approach to visual design has also evolved significantly. Where Through the Darkest of Times used a deliberately stylised aesthetic inspired by German Expressionism, The Darkest Files employs a noir-influenced visual style in an explorable 3D environment that better supports its investigative gameplay while still avoiding photorealistic depictions of atrocities that might trivialize suffering or create an ‘uncanny valley’ effect.

The result is a game that functions more effectively both as entertainment and education, suggesting that the initial framing of Holocaust games as necessarily sacrificing one for the other was always a false dichotomy. Most players engage with the game primarily as a game, while simultaneously absorbing historical knowledge and perspective.

As one reviewer wrote: ‘by the time I finished, I felt like I had just stepped out of a documentary I didn't know I needed to see. It left me feeling angry, sad, and strangely hopeful—because the game's real message isn't just about remembering the past. It's about the importance of telling the truth, even when no one wants to hear it’ (Play3r.net 2025).

This response emphasises how gameplay can evoke complex emotional reactions while conveying profound historical truths—a far cry from the simplistic "important but not good" framing we had received for our earlier games.

Today's Holocaust games demonstrate promising directions, but to fully realise their potential, they must embrace thoughtfully designed mechanics that enhance historical understanding. By developing systems that naturally emerge from the historical material rather than being imposed upon it, developers can create experiences that engage players as active participants in historical investigation and reflection rather than passive recipients of historical information. This approach addresses the provocative question: ‘what would be a productive future for the development of “the Holocaust” as a subject matter for mainstream gaming, and what would be needed to get there?’ The answer lies in creating true games – not merely interactive narratives - where gameplay systems and historical content are seamlessly integrated, where player choices carry meaningful consequences, and where the unique affordances of games as a medium are leveraged to create experiences that other forms of Holocaust education and remembrance cannot provide. This requires continued collaboration between Holocaust institutions and game developers, increased funding for thoughtful projects, and a willingness to push creative boundaries while maintaining historical respect and accuracy.

Remaining Challenges and Future Directions

Despite this progress, significant challenges remain. As noted above, many Holocaust-themed games still often struggle to balance interactivity with historical respect, often erring toward limited player agency in scenarios directly involving Jewish victims or spaces of confinement and mass murder. The result is a landscape where resistance narratives have become increasingly playable, while victim experiences remain largely unplayable.

This imbalance risks reinforcing problematic narratives about Jewish passivity during the Holocaust, inadvertently marginalising the very perspectives games should be working to center. The challenge moving forward will be developing approaches that allow for meaningful player engagement with victim experiences without crossing into exploitative territory.

One of the most significant "red lines" that few developers have crossed is creating gameplay experiences set within concentration camps. This boundary exists for understandable reasons – concerns about trivialising suffering, the risk of turning genocide into a game mechanic, and the fear of creating inappropriate player agency in spaces of historical atrocity. Yet this avoidance has consequences: by making these spaces unplayable, we potentially contribute to their abstraction and distance in cultural memory.

Are there compelling reasons to consider thoughtfully designed games that address life within camps? Perhaps. Such games could help convey the daily reality and humanity of victims, counter the dehumanisation central to Nazi ideology, and provide visceral understanding of historical experiences that text or film cannot. Careful use of mechanics emphasising survival, solidarity, and bearing witness – rather than "winning" or "scoring" – could potentially create meaningful engagement with these difficult histories without exploitation.

Another ongoing challenge is maintaining historical plausibility while creating engaging gameplay. As developers, we've had to make difficult decisions about how to represent complex historical realities within the constraints of game mechanics. These decisions inevitably involve simplification and abstraction, raising questions about how to balance educational fidelity with playability. When creating experiences of persecution and genocide, where should we draw the line between historical accuracy and protection of both players and the dignity of victims?

Finally, there remains the challenge of addressing the Holocaust's uniquely traumatic dimensions through a medium often solely associated with entertainment. While attitudes have evolved significantly, some still question whether any game – no matter how thoughtfully designed – can adequately respect the Holocaust's gravity. This question becomes especially pointed when considering whether there are spaces or experiences from this history that should remain beyond interactive representation altogether.

Conclusion: Genuine Progress, Ongoing Evolution

Returning to the question posed in the provocation – ‘how much have we really moved on from those earlier days when Holocaust computer games were forbidden?’ – the evidence suggests we've moved substantially beyond initial taboos. The landscape has shifted from categorical rejection to nuanced engagement with how, rather than whether, games should address Holocaust history.

This shift reflects growing recognition of games' potential as vehicles for Holocaust education and commemoration, particularly for reaching younger audiences increasingly disconnected from traditional media. It also demonstrates the medium's maturation, as developers have created more sophisticated approaches to balancing playability with historical respect.

Yet this progress should not be mistaken for completion. Many areas remain underexplored, particularly games centered on Jewish experiences, and questions about appropriate limits to interactivity remain unresolved. The evolution of Holocaust games continues, with each new project contributing to our understanding of how interactive media can meaningfully engage with historical trauma.

Looking ahead, the increasing legitimacy of Holocaust-themed games raises new questions worth exploring:

· How can we develop game mechanics that allow players to meaningfully engage with victim experiences without crossing into exploitation?

· What role should survivor testimony play in shaping game narratives, particularly as we transition into a post-survivor era?

· How can we ensure that Holocaust games maintain historical accuracy while still providing engaging experiences for players with varying levels of prior knowledge?

The answers to these questions will shape the next phase in the evolution of Holocaust games – a phase that builds on the hard-won legitimacy these games have achieved while continuing to push the boundaries of how interactive media can contribute to Holocaust memory and education.

Author Bio: Jörg Friedrich is Co-founder and Game Director at Paintbucket Games, developers of historically significant titles including "Through the Darkest of Times," "The Darkest Files," "Remember. The Children of Bullenhuser Damm" and "Forced Abroad" - all exploring different facets of Nazi Germany and its aftermath. His studio creates award-winning games that serve as tools for historical memory. Friedrich also offers workshops and consulting for institutions on developing serious games.